Introduction

So far in this textbook we have discussed two approaches to inference: exact and asymptotic. Both have their strengths and weaknesses. Exact theory provides a useful benchmark but is based on the unrealistic and stringent assumption of the homoskedastic normal regression model. Asymptotic theory provides a more flexible distribution theory but is an approximation with uncertain accuracy.

In this chapter we introduce a set of alternative inference methods which are based around the concept of resampling - which means using sampling information extracted from the empirical distribution of the data. These are powerful methods, widely applicable, and often more accurate than exact methods and asymptotic approximations. Two disadvantages, however, are (1) resampling methods typically require more computation power; and (2) the theory is considerably more challenging. A consequence of the computation requirement is that most empirical researchers use asymptotic approximations for routine calculations while resampling approximations are used for final reporting.

We will discuss two categories of resampling methods used in statistical and econometric practice: jackknife and bootstrap. Most of our attention will be given to the bootstrap as it is the most commonly used resampling method in econometric practice.

The jackknife is the distribution obtained from the leave-one-out estimators (see Section 3.20). The jackknife is most commonly used for variance estimation.

The bootstrap is the distribution obtained by estimation on samples created by i.i.d. sampling with replacement from the dataset. (There are other variants of bootstrap sampling, including parametric sampling and residual sampling.) The bootstrap is commonly used for variance estimation, confidence interval construction, and hypothesis testing.

There is a third category of resampling methods known as sub-sampling which we will not cover in this textbook. Sub-sampling is the distribution obtained by estimation on sub-samples (sampling without replacement) of the dataset. Sub-sampling can be used for most of same purposes as the bootstrap. See the excellent monograph by Politis, Romano and Wolf (1999).

Example

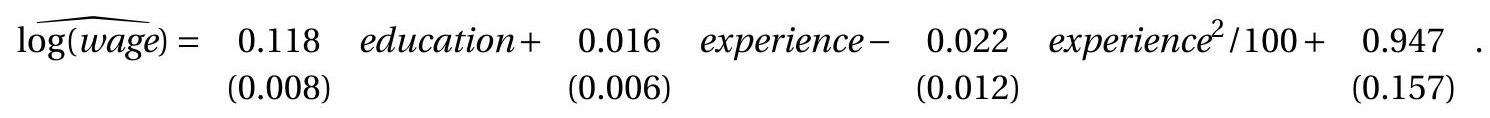

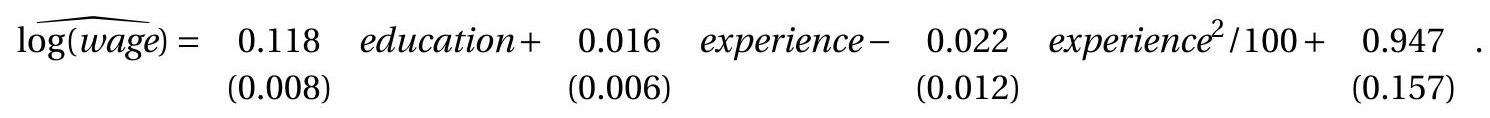

To motivate our discussion we focus on the application presented in Section 3.7, which is a bivariate regression applied to the CPS subsample of married Black female wage earners with 12 years potential work experience and displayed in Table 3.1. The regression equation is

The estimates as reported in (4.44) are

We focus on four estimates constructed from this regression. The first two are the coefficient estimates and . The third is the variance estimate . The fourth is an estimate of the expected level of wages for an individual with 16 years of education (a college graduate), which turns out to be a nonlinear function of the parameters. Under the simplifying assumption that the error is independent of the level of education and normally distributed we find that the expected level of wages is

The final equality is which can be obtained from the normal moment generating function. The parameter is a nonlinear function of the coefficients. The natural estimator of replaces the unknowns by the point estimators. Thus

The standard error for can be found by extending Exercise to find the joint asymptotic distribution of and the slope estimates, and then applying the delta method.

We are interested in calculating standard errors and confidence intervals for the four estimates described above.

Jackknife Estimation of Variance

The jackknife estimates moments of estimators using the distribution of the leave-one-out estimators. The jackknife estimators of bias and variance were introduced by Quenouille (1949) and Tukey (1958), respectively. The idea was expanded further in the monographs of Efron (1982) and Shao and Tu (1995).

Let be any estimator of a vector-valued parameter which is a function of a random sample of size . Let be the variance of . Define the leave-one-out estimators which are computed using the formula for except that observation is deleted. Tukey’s jackknife estimator for is defined as a scale of the sample variance of the leave-one-out estimators:

where is the sample mean of the leave-one-out estimators . For scalar estimators the jackknife standard error is the square root of (10.1): .

A convenient feature of the jackknife estimator is that the formula (10.1) is quite general and does not require any technical (exact or asymptotic) calculations. A downside is that can require separate estimations, which in some cases can be computationally costly.

In most cases will be similar to a robust asymptotic covariance matrix estimator. The main attractions of the jackknife estimator are that it can be used when an explicit asymptotic variance formula is not available and that it can be used as a check on the reliability of an asymptotic formula.

The formula (10.1) is not immediately intuitive so may benefit from some motivation. We start by examining the sample mean for . The leave-one-out estimator is

The sample mean of the leave-one-out estimators is

The difference is

The jackknife estimate of variance (10.1) is then

This is identical to the conventional estimator for the variance of . Indeed, Tukey proposed the scaling in (10.1) so that precisely equals the conventional estimator.

We next examine the case of least squares regression coefficient estimator. Recall from (3.43) that the leave-one-out OLS estimator equals

where and . The sample mean of the leave-one-out estimators is where . Thus . The jackknife estimate of variance for is

where is the HC3 covariance estimator (4.39) based on prediction errors. The second term in (10.5) is typically quite small since is typically small in magnitude. Thus . Indeed the HC3 estimator was originally motivated as a simplification of the jackknife estimator. This shows that for regression coefficients the jackknife estimator of variance is similar to a conventional robust estimator. This is accomplished without the user “knowing” the form of the asymptotic covariance matrix. This is further confirmation that the jackknife is making a reasonable calculation.

Third, we examine the jackknife estimator for a function of a least squares estimator. The leave-one-out estimator of is

The second equality is (10.4). The final approximation is obtained by a mean-value expansion, using and setting . This approximation holds in large samples because are uniformly consistent for . The jackknife variance estimator for thus equals

The final line equals a delta-method estimator for the variance of constructed with the covariance estimator (4.39). This shows that the jackknife estimator of variance for is approximately an asymptotic delta-method estimator. While this is an asymptotic approximation, it again shows that the jackknife produces an estimator which is asymptotically similar to one produced by asymptotic methods. This is despite the fact that the jackknife estimator is calculated without reference to asymptotic theory and does not require calculation of the derivatives of .

This argument extends directly to any “smooth function” estimator. Most of the estimators discussed so far in this textbook take the form where and is some vector-valued function of the data. For any such estimator the leave-one-out estimator equals and its jackknife estimator of variance is (10.1). Using (10.2) and a mean-value expansion we have the largesample approximation

where . Thus

and the jackknife estimator of the variance of approximately equals

where as defined in (10.3) is the conventional (and jackknife) estimator for the variance of . Thus is approximately the delta-method estimator. Once again, we see that the jackknife estimator automatically calculates what is effectively the delta-method variance estimator, but without requiring the user to explicitly calculate the derivative of .

Example

We illustrate by reporting the asymptotic and jackknife standard errors for the four parameter estimates given earlier. In Table we report the actual values of the leave-one-out estimates for each of the twenty observations in the sample. The jackknife standard errors are calculated as the scaled square roots of the sample variances of these leave-one-out estimates and are reported in the second-to-last row. For comparison the asymptotic standard errors are reported in the final row.

For all estimates the jackknife and asymptotic standard errors are quite similar. This reinforces the credibility of both standard error estimates. The largest differences arise for and , whose jackknife standard errors are about larger than the asymptotic standard errors.

The take-away from our presentation is that the jackknife is a simple and flexible method for variance and standard error calculation. Circumventing technical asymptotic and exact calculations, the jackknife produces estimates which in many cases are similar to asymptotic delta-method counterparts. The jackknife is especially appealing in cases where asymptotic standard errors are not available or are difficult to calculate. They can also be used as a double-check on the reasonableness of asymptotic delta-method calculations.

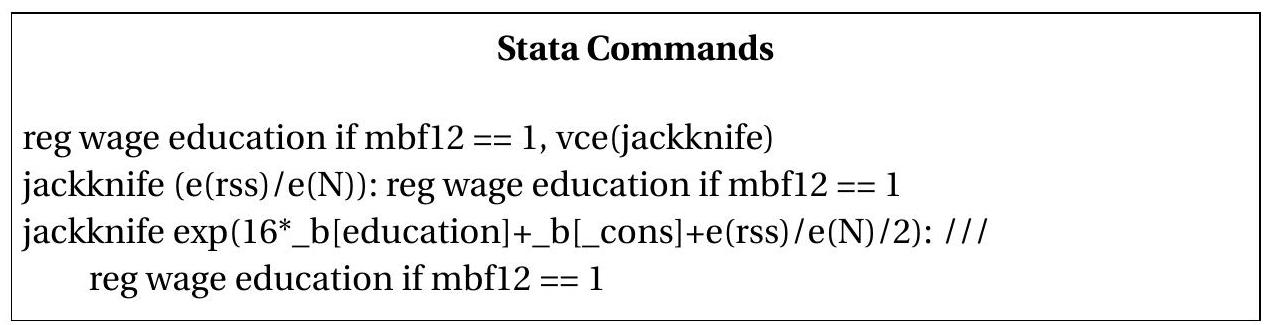

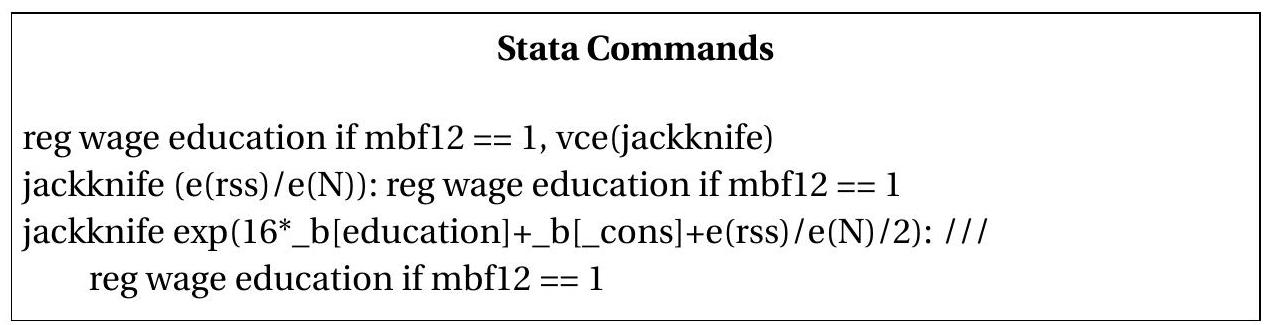

In Stata, jackknife standard errors for coefficient estimates in many models are obtained by the vce(jackknife) option. For nonlinear functions of the coefficients or other estimators the jackkn ife command can be combined with any other command to obtain jackknife standard errors.

To illustrate, below we list the Stata commands which calculate the jackknife standard errors listed above. The first line is least squares estimation with standard errors calculated by the jackknife. The second line calculates the error variance estimate with a jackknife standard error. The third line does the same for the estimate .

Table 10.1: Leave-one-out Estimators and Jackknife Standard Errors

| 1 |

|

|

|

|

| 2 |

|

|

|

|

| 3 |

|

|

|

|

| 4 |

|

|

|

|

| 5 |

|

|

|

|

| 6 |

|

|

|

|

| 7 |

|

|

|

|

| 8 |

|

|

|

|

| 9 |

|

|

|

|

| 10 |

|

|

|

|

| 11 |

|

|

|

|

| 12 |

|

|

|

|

| 13 |

|

|

|

|

| 14 |

|

|

|

|

| 15 |

|

|

|

|

| 16 |

|

|

|

|

| 17 |

|

|

|

|

| 18 |

|

|

|

|

| 19 |

|

|

|

|

| 20 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Jackknife for Clustered Observations

In Section we introduced the clustered regression model, cluster-robust variance estimators, and cluster-robust standard errors. Jackknife variance estimation can also be used for clustered samples but with some natural modifications. Recall that the least squares estimator in the clustered sample context can be written as

where indexes the cluster. Instead of leave-one-out estimators, it is natural to use deletecluster estimators, which delete one cluster at a time. They take the form (4.58):

where

The delete-cluster jackknife estimator of the variance of is

We call a cluster-robust jackknife estimator of variance.

Using the same approximations as the previous section we can show that the delete-cluster jackknife estimator is asymptotically equivalent to the cluster-robust covariance matrix estimator (4.59) calculated with the delete-cluster prediction errors. This verifies that the delete-cluster jackknife is the appropriate jackknife approach for clustered dependence.

For parameters which are functions of the least squares estimator, the delete-cluster jackknife estimator of the variance of is

Using a mean-value expansion we can show that this estimator is asymptotically equivalent to the deltamethod cluster-robust covariance matrix estimator for . This shows that the jackknife estimator is appropriate for covariance matrix estimation.

As in the context of i.i.d. samples, one advantage of the jackknife covariance matrix estimators is that they do not require the user to make a technical calculation of the asymptotic distribution. A downside is an increase in computation cost, as separate regressions are effectively estimated.

In Stata, jackknife standard errors for coefficient estimates with clustered observations are obtained by using the options cluster (id) vce(jackkn ife) where id denotes the cluster variable.

The Bootstrap Algorithm

The bootstrap is a powerful approach to inference and is due to the pioneering work of Efron (1979). There are many textbook and monograph treatments of the bootstrap, including Efron (1982), Hall (1992), Efron and Tibshirani (1993), Shao and Tu (1995), and Davison and Hinkley (1997). Reviews for econometricians are provided by Hall (1994) and Horowitz (2001)

There are several ways to describe or define the bootstrap and there are several forms of the bootstrap. We start in this section by describing the basic nonparametric bootstrap algorithm. In subsequent sections we give more formal definitions of the bootstrap as well as theoretical justifications.

Briefly, the bootstrap distribution is obtained by estimation on independent samples created by i.i.d. sampling (sampling with replacement) from the original dataset.

To understand this it is useful to start with the concept of sampling with replacement from the dataset. To continue the empirical example used earlier in the chapter we focus on the dataset displayed in Table 3.1, which has observations. Sampling from this distribution means randomly selecting one row from this table. Mathematically this is the same as randomly selecting an integer from the set . To illustrate, MATLAB has a random integer generator (the function randi). Using the random number seed of 13 (an arbitrary choice) we obtain the random draw 16 . This means that we draw observation number 16 from Table 3.1. Examining the table we can see that this is an individual with wage and education of 16 years. We repeat by drawing another random integer on the set and this time obtain 5 . This means we take observation 5 from Table 3.1, which is an individual with wage and education of 16 years. We continue until we have such draws. This random set of observations are . We call this the bootstrap sample.

Notice that the observations each appear twice in the bootstrap sample, and the observations do not appear at all. That is okay. In fact, it is necessary for the bootstrap to work. This is because we are drawing with replacement. (If we instead made draws without replacement then the constructed dataset would have exactly the same observations as in Table 3.1, only in different order.) We can also ask the question “What is the probability that an individual observation will appear at least once in the bootstrap sample?” The answer is

The limit holds as . The approximation is excellent even for small . For example, when the probability (10.6) is . These calculations show that an individual observation is in the bootstrap sample with probability near .

Once again, the bootstrap sample is the constructed dataset with the 20 observations drawn randomly from the original sample. Notationally, we write the bootstrap observation as and the bootstrap sample as . In our present example with denoting the log wage the bootstrap sample is

The bootstrap estimate is obtained by applying the least squares estimation formula to the bootstrap sample. Thus we regress on . The other bootstrap estimates, in our example and , are obtained by applying their estimation formulae to the bootstrap sample as well. Writing we have the bootstrap estimate of the parameter vector . In our example (the bootstrap sample described above) . This is one draw from the bootstrap distribution of the estimates.

The estimate as described is one random draw from the distribution of estimates obtained by i.i.d. sampling from the original data. With one draw we can say relatively little. But we can repeat this exercise to obtain multiple draws from this bootstrap distribution. To distinguish between these draws we index the bootstrap samples by , and write the bootstrap estimates as or .

To continue our illustration we draw 20 more random integers , and construct a second bootstrap sample. On this sample we again estimate the parameters and obtain . This is a second random draw from the distribution of . We repeat this times, storing the parameter estimates . We have thus created a new dataset of bootstrap draws . By construction the draws are independent across and identically distributed.

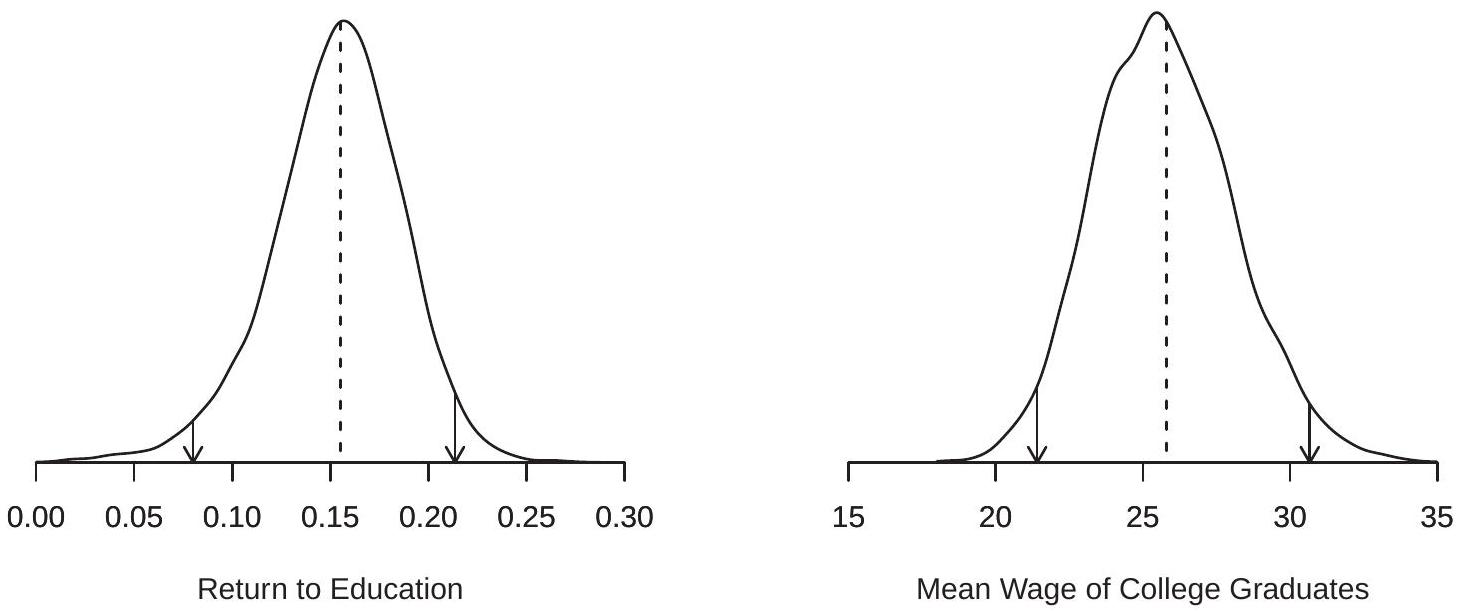

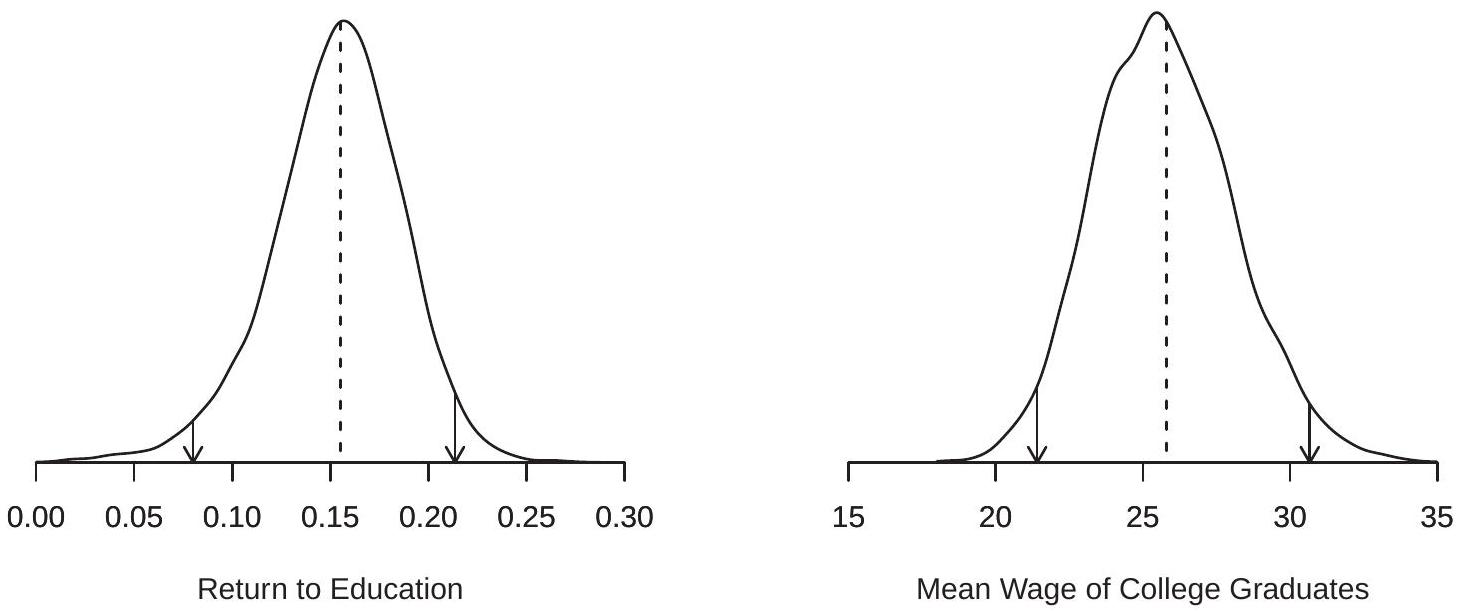

The number of bootstrap draws, , is often called the “number of bootstrap replications”. Typical choices for are 1000,5000 , and 10,000. We discuss selecting later, but roughly speaking, larger results in a more precise estimate at an increased computation cost. For our application we set 10,000 . To illustrate, Figure displays the densities of the distributions of the bootstrap estimates and across 10,000 draws. The dashed lines show the point estimate. You can notice that the density for is slightly skewed to the left.\

Figure 10.1: Bootstrap Distributions of and

Bootstrap Variance and Standard Errors

Given the bootstrap draws we can estimate features of the bootstrap distribution. The bootstrap estimator of variance of an estimator is the sample variance across the bootstrap draws . It equals

For a scalar estimator the bootstrap standard error is the square root of the bootstrap estimator of variance:

This is a very simple statistic to calculate and is the most common use of the bootstrap in applied econometric practice. A caveat (discussed in more detail in Section 10.15) is that in many cases it is better to use a trimmed estimator.

Standard errors are conventionally reported to convey the precision of the estimator. They are also commonly used to construct confidence intervals. Bootstrap standard errors can be used for this purpose. The normal-approximation bootstrap confidence interval is

where is the quantile of the distribution. This interval is identical in format to an asymptotic confidence interval, but with the bootstrap standard error replacing the asymptotic standard error. is the default confidence interval reported by Stata when the bootstrap has been used to calculate standard errors. However, the normal-approximation interval is in general a poor choice for confidence interval construction as it relies on the normal approximation to the t-ratio which can be inaccurate in finite samples. There are other methods - such as the bias-corrected percentile method to be discussed in Section - which are just as simple to compute but have better performance. In general, bootstrap standard errors should be used as estimates of precision rather than as tools to construct confidence intervals.

Since is finite, all bootstrap statistics, such as , are estimates and hence random. Their values will vary across different choices for and simulation runs (depending on how the simulation seed is set). Thus you should not expect to obtain the exact same bootstrap standard errors as other researchers when replicating their results. They should be similar (up to simulation sampling error) but not precisely the same.

In Table we report the four parameter estimates introduced in Section along with asymptotic, jackknife and bootstrap standard errors. We also report four bootstrap confidence intervals which will be introduced in subsequent sections.

For these four estimators we can see that the bootstrap standard errors are quite similar to the asymptotic and jackknife standard errors. The most noticable difference arises for , where the bootstrap standard error is about larger than the asymptotic standard error.

Table 10.2: Comparison of Methods

| Estimate |

|

|

|

|

| Asymptotic s.e. |

|

|

|

|

| Jackknife s.e. |

|

|

|

|

| Bootstrap s.e. |

|

|

|

|

| Percentile Interval |

|

|

|

|

| BC Percentile Interval |

|

|

|

|

| BC |

|

|

|

|

In Stata, bootstrap standard errors for coefficient estimates in many models are obtained by the vce(bootstrap, reps(#)) option, where # is the number of bootstrap replications. For nonlinear functions of the coefficients or other estimators the bootstrap command can be combined with any other command to obtain bootstrap standard errors. Synonyms for bootstrap are bstrap and bs.

To illustrate, below we list the Stata commands which will calculate the bootstrap standard errors listed above.

They will not precisely replicate the standard errors since those in Table were produced in Matlab which uses a different random number sequence.

Stata Commands reg wage education if , vce(bootstrap, reps

bs (e(rss)/e(N)), reps(10000): reg wage education if

bs ( bb[education]+_b[_cons] , reps(10000): ///

reg wage education if

Percentile Interval

The second most common use of bootstrap methods is for confidence intervals. There are multiple bootstrap methods to form confidence intervals. A popular and simple method is called the percentile interval. It is based on the quantiles of the bootstrap distribution.

In Section we described the bootstrap algorithm which creates an i.i.d. sample of bootstrap estimates corresponding to an estimator of a parameter . We focus on the case of a scalar parameter .

For any we can calculate the empirical quantile of these bootstrap estimates. This is the number such that bootstrap estimates are smaller than , and is typically calculated by taking the order statistic of the . See Section of Probability and Statistics for Economists for a precise discussion of empirical quantiles and common quantile estimators.

The percentile bootstrap confidence interval is

For example, if , and the empirical quantile estimator is used, then .

To illustrate, the and quantiles of the bootstrap distributions of and are indicated in Figure by the arrows. The intervals between the arrows are the percentile intervals.

The percentile interval has the convenience that it does not require calculation of a standard error. This is particularly convenient in contexts where asymptotic standard error calculation is complicated, burdensome, or unknown. is a simple by-product of the bootstrap algorithm and does not require meaningful computational cost above that required to calculate the bootstrap standard error.

The percentile interval has the useful property that it is transformation-respecting. Take a monotone parameter transformation . The percentile interval for is simply the percentile interval for mapped by . That is, if is the percentile interval for , then is the percentile interval for . This property follows directly from the equivariance property of sample quantiles. Many confidence-interval methods, such as the delta-method asymptotic interval and the normal-approximation interval , do not share this property.

To illustrate the usefulness of the transformation-respecting property consider the variance . In some cases it is useful to report the variance and in other cases it is useful to report the standard deviation . Thus we may be interested in confidence intervals for or . To illustrate, the asymptotic normal confidence interval for which we calculate from Table is . Taking square roots we obtain an interval for of [0.244,0.477]. Alternatively, the delta method standard error for is , leading to an asymptotic confidence interval for of which is different. This shows that the delta method is not transformation-respecting. In contrast, the percentile interval for is and that for is which is identical to the square roots of the interval for .

The bootstrap percentile intervals for the four estimators are reported in Table 13.2. In Stata, percentile confidence intervals can be obtained by using the command estat bootstrap, percentile or the command estat bootstrap, all after an estimation command which calculates standard errors via the bootstrap.

The Bootstrap Distribution

For applications it is often sufficient if one understands the bootstrap as an algorithm. However, for theory it is more useful to view the bootstrap as a specific estimator of the sampling distribution. For this it is useful to introduce some additional notation.

The key is that the distribution of any estimator or statistic is determined by the distribution of the data. While the latter is unknown it can be estimated by the empirical distribution of the data. This is what the bootstrap does.

To fix notation, let denote the distribution of an individual observation . (In regression, is the .) Let denote the distribution of an estimator . That is,

We write the distribution as a function of and since the latter (generally) affect the distribution of . We are interested in the distribution . For example, we want to know its variance to calculate a standard error or its quantiles to calculate a percentile interval.

In principle, if we knew the distribution we should be able to determine the distribution . In practice there are two barriers to implementation. The first barrier is that the calculation of is generally infeasible except in certain special cases such as the normal regression model. The second barrier is that in general we do not know .

The bootstrap simultaneously circumvents these two barriers by two clever ideas. First, the bootstrap proposes estimation of by the empirical distribution function (EDF) , which is the simplest nonparametric estimator of the joint distribution of the observations. The EDF is . (See Section of Probability and Statistics for Economists for details and properties.) Replacing with we obtain the idealized bootstrap estimator of the distribution of

The bootstrap’s second clever idea is to estimate by simulation. This is the bootstrap algorithm described in the previous sections. The essential idea is that simulation from is sampling with replacement from the original data, which is computationally simple. Applying the estimation formula for we obtain i.i.d. draws from the distribution . By making a large number of such draws we can estimate any feature of of interest. The bootstrap combines these two ideas: (1) estimate by ; (2) estimate by simulation. These ideas are intertwined. Only by considering these steps together do we obtain a feasible method.

The way to think about the connection between and is as follows. is the distribution of the estimator obtained when the observations are sampled i.i.d. from the population distribution . is the distribution of the same statistic, denoted , obtained when the observations are sampled i.i.d. from the empirical distribution . It is useful to conceptualize the “universe” which separately generates the dataset and the bootstrap sample. The “sampling universe” is the population distribution . In this universe the true parameter is . The “bootstrap universe” is the empircal distribution . When drawing from the bootstrap universe we are treating as if it is the true distribution. Thus anything which is true about should be treated as true in the bootstrap universe. In the bootstrap universe the “true” value of the parameter is the value determined by the EDF . In most cases this is the estimate . It is the true value of the coefficient when the true distribution is . We now carefully explain the connection with the bootstrap algorithm as previously described.

First, observe that sampling with replacement from the sample is identical to sampling from the EDF . This is because the EDF is the probability distribution which puts probability mass on each observation. Thus sampling from means sampling an observation with probability , which is sampling with replacement.

Second, observe that the bootstrap estimator described here is identical to the bootstrap algorithm described in Section 10.6. That is, is the random vector generated by applying the estimator formula to samples obtained by random sampling from .

Third, observe that the distribution of these bootstrap estimators is the bootstrap distribution (10.9). This is a precise equality. That is, the bootstrap algorithm generates i.i.d. samples from , and when the estimators are applied we obtain random variables with the distribution .

Fourth, observe that the bootstrap statistics described earlier - bootstrap variance, standard error, and quantiles - are estimators of the corresponding features of the bootstrap distribution .

This discussion is meant to carefully describe why the notation is useful to help understand the properties of the bootstrap algorithm. Since is the natural nonparametric estimator of the unknown distribution is the natural plug-in estimator of the unknown . Furthermore, because is uniformly consistent for by the Glivenko-Cantelli Lemma (Theorem in Probability and Statistics for Economists) we also can expect to be consistent for . Making this precise is a bit challenging since and are functions. In the next several sections we develop an asymptotic distribution theory for the bootstrap distribution based on extending asymptotic theory to the case of conditional distributions.

The Distribution of the Bootstrap Observations

Let be a random draw from the sample . What is the distribution of ?

Since we are fixing the observations, the correct question is: What is the conditional distribution of , conditional on the observed data? The empirical distribution function summarizes the information in the sample, so equivalently we are talking about the distribution conditional on . Consequently we will write the bootstrap probability function and expectation as

Notationally, the starred distribution and expectation are conditional given the data.

The (conditional) distribution of is the empirical distribution function , which is a discrete distribution with mass points on each observation . Thus even if the original data come from a continuous distribution, the bootstrap data distribution is discrete.

The (conditional) mean and variance of are calculated from the EDF, and equal the sample mean and variance of the data. The mean is

and the variance is

To summarize, the conditional distribution of , given , is the discrete distribution on with mean and covariance matrix .

We can extend this analysis to any integer moment . Assume is scalar. The moment of is

the sample moment. The central moment of is

the central sample moment. Similarly, the cumulant of is , the sample cumulant.

The Distribution of the Bootstrap Sample Mean

The bootstrap sample mean is

We can calculate its (conditional) mean and variance. The mean is

using (10.10). Thus the bootstrap sample mean has a distribution centered at the sample mean . This is because the bootstrap observations are drawn from the bootstrap universe, which treats the EDF as the truth, and the mean of the latter distribution is .

The (conditional) variance of the bootstrap sample mean is

using (10.11). In the scalar case, . This shows that the bootstrap variance of is precisely described by the sample variance of the original observations. Again, this is because the bootstrap observations are drawn from the bootstrap universe.

We can extend this to any integer moment . Assume is scalar. Define the normalized bootstrap sample mean . Using expressions from Section of Probability and Statistics for Economists, the through conditional moments of are

where is the sample cumulant. Similar expressions can be derived for higher moments. The moments (10.14) are exact, not approximations.

Bootstrap Asymptotics

The bootstrap mean is a sample average over i.i.d. random variables, so we might expect it to converge in probability to its expectation. Indeed, this is the case, but we have to be a bit careful since the bootstrap mean has a conditional distribution (given the data) so we need to define convergence in probability for conditional distributions.

Definition We say that a random vector converges in bootstrap probability to as , denoted , if for all

To understand this definition recall that conventional convergence in probability means that for a sufficiently large sample size , the probability is high that is arbitrarily close to its limit . In contrast, Definition says means that for a sufficiently large , the probability is high that the conditional probability that is close to its limit is high. Note that there are two uses of probability - both unconditional and conditional.

Our label “convergence in bootstrap probability” is a bit unusual. The label used in much of the statistical literature is “convergence in probability, in probability” but that seems like a mouthful. That literature more often focuses on the related concept of “convergence in probability, almost surely” which holds if we replace the ” convergence with almost sure convergence. We do not use this concept in this chapter as it is an unnecessary complication.

While we have stated Definition for the specific conditional probability distribution , the idea is more general and can be used for any conditional distribution and any sequence of random vectors.

The following may seem obvious but it is useful to state for clarity. Its proof is given in Section

Theorem If as then .

Given Definition 10.1, we can establish a law of large numbers for the bootstrap sample mean. Theorem Bootstrap WLLN. If are independent and uniformly integrable then and as .

The proof (presented in Section 10.31) is somewhat different from the classical case as it is based on the Marcinkiewicz WLLN (Theorem 10.20, presented in Section 10.31).

Notice that the conditions for the bootstrap WLLN are the same for the conventional WLLN. Notice as well that we state two related but slightly different results. The first is that the difference between the bootstrap sample mean and the sample mean diminishes as the sample size diverges. The second result is that the bootstrap sample mean converges to the population mean . The latter is not surprising (since the sample mean converges in probability to ) but it is constructive to be precise since we are dealing with a new convergence concept.

Theorem 10.3 Bootstrap Continuous Mapping Theorem. If as and is continuous at , then as .

The proof is essentially identical to that of Theorem so is omitted.

We next would like to show that the bootstrap sample mean is asymptotically normally distributed, but for that we need a definition of convergence for conditional distributions.

Definition Let be a sequence of random vectors with conditional distributions . We say that converges in bootstrap distribution to as , denoted , if for all at which is continuous, as .

The difference with the conventional definition is that Definition treats the conditional distribution as random. An alternative label for Definition is “convergence in distribution, in probability”.

We now state a CLT for the bootstrap sample mean, with a proof given in Section 10.31.

Theorem 10.4 Bootstrap CLT. If are i.i.d., , and , then as .

Theorem shows that the normalized bootstrap sample mean has the same asymptotic distribution as the sample mean. Thus the bootstrap distribution is asymptotically the same as the sampling distribution. A notable difference, however, is that the bootstrap sample mean is normalized by centering at the sample mean, not at the population mean. This is because is the true mean in the bootstrap universe.

We next state the distributional form of the continuous mapping theorem for bootstrap distributions and the Bootstrap Delta Method. Theorem 10.5 Bootstrap Continuous Mapping Theorem

If as and has the set of discontinuity points such that , then as .

Theorem 10.6 Bootstrap Delta Method: If , and is continuously differentiable in a neighborhood of , then as

where and . In particular, if then as

For a proof, see Exercise 10.7.

We state an analog of Theorem 6.10, which presented the asymptotic distribution for general smooth functions of sample means, which covers most econometric estimators.

Theorem 10.7 Under the assumptions of Theorem 6.10, that is, if is i.i.d., , and is continuous in a neighborhood of , for with and with , as

where and .

For a proof, see Exercise 10.8.

Theorem shows that the asymptotic distribution of the bootstrap estimator is identical to that of the sample estimator . This means that we can learn the distribution of from the bootstrap distribution, and hence perform asymptotically correct inference.

For some bootstrap applications we use bootstrap estimates of variance. The plug-in estimator of is where and

The bootstrap version is

Application of the bootstrap WLLN and bootstrap CMT show that is consistent for .

Theorem Under the assumptions of Theorem 10.7, as .

For a proof, see Exercise 10.9.

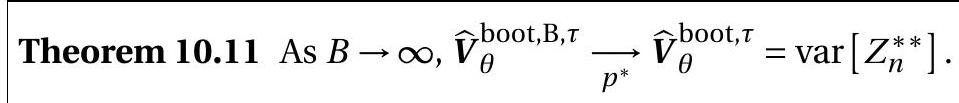

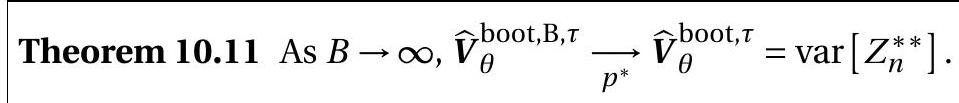

Consistency of the Bootstrap Estimate of Variance

Recall the definition (10.7) of the bootstrap estimator of variance of an estimator . In this section we explore conditions under which is consistent for the asymptotic variance of .

To do so it is useful to focus on a normalized version of the estimator so that the asymptotic variance is not degenerate. Suppose that for some sequence we have

and

for some limit distribution . That is, for some normalization, both and have the same asymptotic distribution. This is quite general as it includes the smooth function model. The conventional bootstrap estimator of the variance of is the sample variance of the bootstrap draws . This equals the estimator (10.7) multiplied by . Thus it is equivalent (up to scale) whether we discuss estimating the variance of or .

The bootstrap estimator of variance of is

Notice that we index the estimator by the number of bootstrap replications .

Since converges in bootstrap distribution to the same asymptotic distribution as , it seems reasonable to guess that the variance of will converge to that of . However, convergence in distribution is not sufficient for convergence in moments. For the variance to converge it is also necessary for the sequence to be uniformly square integrable. Theorem If (10.15) and (10.16) hold for some sequence and is uniformly integrable, then as

and as

This raises the question: Is the normalized sequence uniformly integrable? We spend the remainder of this section exploring this question and turn in the next section to trimmed variance estimators which do not require uniform integrability.

This condition is reasonably straightforward to verify for the case of a scalar sample mean with a finite variance. That is, suppose and . In (10.14) we calculated the exact fourth central moment of :

where and . The assumption implies that so . Furthermore, by the Marcinkiewicz WLLN (Theorem 10.20). It follows that

Theorem shows that this implies that is uniformly integrable. Thus if has a finite variance the normalized bootstrap sample mean is uniformly square integrable and the bootstrap estimate of variance is consistent by Theorem .

Now consider the smooth function model of Theorem 10.7. We can establish the following result.

Theorem 10.10 In the smooth function model of Theorem 10.7, if for some the -order derivatives of are bounded, then is uniformly square integrable and the bootstrap estimator of variance is consistent as in Theorem 10.9.

For a proof see Section .

This shows that the bootstrap estimate of variance is consistent for a reasonably broad class of estimators. The class of functions covered by this result includes all -order polynomials.

Trimmed Estimator of Bootstrap Variance

Theorem showed that the bootstrap estimator of variance is consistent for smooth functions with a bounded order derivative. This is a fairly broad class but excludes many important applications. An example is where and . This function does not have a bounded derivative (unless is bounded away from zero) so is not covered by Theorem 10.10. This is more than a technical issue. When are jointly normally distributed then it is known that does not possess a finite variance. Consequently we cannot expect the bootstrap estimator of variance to perform well. (It is attempting to estimate the variance of , which is infinity.)

In these cases it is preferred to use a trimmed estimator of bootstrap variance. Let be a sequence of positive trimming numbers satisfying . Define the trimmed statistic

The trimmed bootstrap estimator of variance is

We first examine the behavior of as the number of bootstrap replications grows to infinity. It is a sample variance of independent bounded random vectors. Thus by the bootstrap WLLN (Theorem 10.2) converges in bootstrap probability to the variance of .

We next examine the behavior of the bootstrap estimator as grows to infinity. We focus on the smooth function model of Theorem 10.7, which showed that . Since the trimming is asymptotically negligible, it follows that . If we can show that is uniformly square integrable, Theorem shows that as . This is shown in the following result, whose proof is presented in Section 10.31.

Theorem Under the assumptions of Theorem 10.7,

Theorems and show that the trimmed bootstrap estimator of variance is consistent for the asymptotic variance in the smooth function model, which includes most econometric estimators. This justifies bootstrap standard errors as consistent estimators for the asymptotic distribution.

An important caveat is that these results critically rely on the trimmed variance estimator. This is a critical caveat as conventional statistical packages (e.g. Stata) calculate bootstrap standard errors using the untrimmed estimator (10.7). Thus there is no guarantee that the reported standard errors are consistent. The untrimmed variance estimator works in the context of Theorem and whenever the bootstrap statistic is uniformly square integrable, but not necessarily in general applications.

In practice, it may be difficult to know how to select the trimming sequence . The rule does not provide practical guidance. Instead, it may be useful to think about trimming in terms of percentages of the bootstrap draws. Thus we can set so that a given small percentage is trimmed. For theoretical interpretation we would set as . In practice we might set .

Unreliability of Untrimmed Bootstrap Standard Errors

In the previous section we presented a trimmed bootstrap variance estimator which should be used to form bootstrap standard errors for nonlinear estimators. Otherwise, the untrimmed estimator is potentially unreliable.

This is an unfortunate situation, because reporting of bootstrap standard errors is commonplace in contemporary applied econometric practice, and standard applications (including Stata) use the untrimmed estimator.

To illustrate the seriousness of the problem we use the simple wage regression (7.31) which we repeat here. This is the subsample of married Black women with 982 observations. The point estimates and standard errors are

We are interested in the experience level which maximizes expected log wages . The point estimate and standard errors calculated with different methods are reported in Table below.

The point estimate of the experience level with maximum earnings is . The asymptotic and jackknife standard errors are about 7 . The bootstrap standard error, however, is 825 ! Confused by this unusual value we rerun the bootstrap and obtain a standard error of 544 . Each was computed with 10,000 bootstrap replications. The fact that the two bootstrap standard errors are considerably different when recomputed (with different starting seeds) is indicative of moment failure. When there is an enormous discrepancy like this between the asymptotic and bootstrap standard error, and between bootstrap runs, it is a signal that there may be moment failure and consequently bootstrap standard errors are unreliable.

A trimmed bootstrap with (set to slightly exceed three asymptotic standard errors) produces a more reasonable standard error of

One message from this application is that when different methods produce very different standard errors we should be cautious about trusting any single method. The large discrepancies indicate poor asymptotic approximations, rendering all methods inaccurate. Another message is to be cautious about reporting conventional bootstrap standard errors. Trimmed versions are preferred, especially for nonlinear functions of estimated coefficients.

Table 10.3: Experience Level Which Maximizes Expected log Wages

| Asymptotic s.e. |

|

| Jackknife s.e. |

|

| Bootstrap s.e. (standard) |

|

| Bootstrap s.e. (repeat) |

|

| Bootstrap s.e. (trimmed) |

|

Consistency of the Percentile Interval

Recall the percentile interval (10.8). We now provide conditions under which it has asymptotically correct coverage. Theorem Assume that for some sequence

and

where is continuously distributed and symmetric about zero. Then as

The assumptions (10.18)-(10.19) hold for the smooth function model of Theorem 10.7, so this result incorporates many applications. The beauty of Theorem is that the simple confidence interval - which does not require technical calculation of asymptotic standard errors - has asymptotically valid coverage for any estimator which falls in the smooth function class, as well as any other estimator satisfying the convergence results (10.18)-(10.19) with symmetrically distributed. The conditions are weaker than those required for consistent bootstrap variance estimation (and normal-approximation confidence intervals) because it is not necessary to verify that is uniformly integrable, nor necessary to employ trimming.

The proof of Theorem is not difficult. The convergence assumption (10.19) implies that the quantile of , which is by quantile equivariance, converges in probability to the quantile of , which we can denote as . Thus

Let be the distribution function of . The assumption of symmetry implies . Then the percentile interval has coverage

The convergence holds by (10.18) and (10.20). The following equality uses the definition of , the nextto-last is the symmetry of , and the final equality is the definition of . This establishes Theorem

Theorem seems quite general, but it critically rests on the assumption that the asymptotic distribution is symmetrically distributed about zero. This may seem innocuous since conventional asymptotic distributions are normal and hence symmetric, but it deserves further scrutiny. It is not merely a technical assumption - an examination of the steps in the preceeding argument isolate quite clearly that if the symmetry assumption is violated then the asymptotic coverage will not be . While Theorem does show that the percentile interval is asymptotically valid for a conventional asymptotically normal estimator, the reliance on symmetry in the argument suggests that the percentile method will work poorly when the finite sample distribution is asymmetric. This turns out to be the case and leads us to consider alternative methods in the following sections. It is also worthwhile to investigate a finite sample justification for the percentile interval based on a heuristic analogy due to Efron.

Assume that there exists an unknown but strictly increasing transformation such that has a pivotal distribution (does not vary with ) which is symmetric about zero. For example, if we can set . Alternatively, if and then we can set

To assess the coverage of the percentile interval, observe that since the distribution is pivotal the bootstrap distribution also has distribution . Let be the quantile of the distribution . Since is the quantile of the distribution of and is a monotonic transformation of , by the quantile equivariance property we deduce that . The percentile interval has coverage

The second equality applies the monotonic transformation to all elements. The fourth uses the relationship . The fifth uses the defintion of . The sixth uses the symmetry property of , and the final is by the definition of as the quantile of .

This calculation shows that under these assumptions the percentile interval has exact coverage . The nice thing about this argument is the introduction of the unknown transformation for which the percentile interval automatically adapts. The unpleasant feature is the assumption of symmetry. Similar to the asymptotic argument the calculation strongly relies on the symmetry of distribution . Without symmetry the coverage will be incorrect.

Intuitively, we expect that when the assumptions are approximately true then the percentile interval will have approximately correct coverage. Thus so long as there is a transformation such that is approximately pivotal and symmetric about zero, then the percentile interval should work well.

This argument has the following application. Suppose that the parameter of interest is where and suppose has a pivotal symmetric distribution about . Then even though does not have a symmetric distribution, the percentile interval applied to will have the correct coverage, because the monotonic transformation has a pivotal symmetric distribution.

Bias-Corrected Percentile Interval

The accuracy of the percentile interval depends critically upon the assumption that the sampling distribution is approximately symmetrically distributed. This excludes finite sample bias, for an estimator which is biased cannot be symmetrically distributed. Many contexts in which we want to apply bootstrap methods (rather than asymptotic) are when the parameter of interest is a nonlinear function of the model parameters, and nonlinearity typically induces estimation bias. Consequently it is difficult to expect the percentile method to generally have accurate coverage.

To reduce the bias problem Efron (1982) introduced the bias-corrected (BC) percentile interval. The justification is heuristic but there is considerable evidence that the bias-corrected method is an important improvement on the percentile interval. The construction is based on the assumption is that there is a an unknown but strictly increasing transformation and unknown constant such that

(The assumption that is normal is not critical. It could be replaced by any known symmetric and invertible distribution.) Let denote the normal distribution function, its quantile function, and the normal critical values. Then the BC interval can be constructed from the bootstrap estimators and bootstrap quantiles as follows. Set

and

is a measure of median bias, and is transformed into normal units. If the bias of is zero then and . If is upwards biased then and . Conversely if is dowward biased then and . Define for any an adjusted version

If then . If then , and conversely when . The BC interval is

Essentially, rather than going from the to quantile, the BC interval uses adjusted quantiles, with the degree of adjustment depending on the extent of the bias.

The construction of the BC interval is not intuitive. We now show that assumption (10.21) implies that the BC interval has exact coverage. (10.21) implies that

Since the distribution is pivotal the result carries over to the bootstrap distribution

Evaluating (10.26) at we find which implies . Inverting, we obtain

which is the probability limit of (10.23) as . Thus the unknown is recoved by (10.23), and we can treat as if it were known.

From (10.26) we deduce that

This equation shows that equals the bootstrap quantile. That is, . Hence we can write (10.25) as

It has coverage probability

The second equality applies the transformation . The fourth equality uses the model (10.21) and the fact . This shows that the BC interval (10.25) has exact coverage under the assumption (10.21).

Furthermore, under the assumptions of Theorem 10.13, the interval has asymptotic coverage probability , since the bias correction is asymptotically negligible.

An important property of the BC percentile interval is that it is transformation-respecting (like the percentile interval). To see this, observe that is invariant to transformations because it is a probability, and thus and are invariant. Since the interval is constructed from the and quantiles, the quantile equivariance property shows that the interval is transformation-respecting.

The bootstrap BC percentile intervals for the four estimators are reported in Table 13.2. They are generally similar to the percentile intervals, though the intervals for and are somewhat shifted to the right.

In Stata, BC percentile confidence intervals can be obtained by using the command estat bootstrap after an estimation command which calculates standard errors via the bootstrap.

Percentile Interval

A further improvement on the BC interval was made by Efron (1987) to account for the skewness in the sampling distribution, which can be modeled by specifying that the variance of the estimator depends on the parameter. The resulting bootstrap accelerated bias-corrected percentile interval has improved performance on the BC interval, but requires a bit more computation and is less intuitive to understand.

The construction is a generalization of that for the BC intervals. The assumption is that there is an unknown but strictly increasing transformation and unknown constants and such that

(As before, the assumption that is normal could be replaced by any known symmetric and invertible distribution.)

The constant is estimated by (10.23) just as for the BC interval. There are several possible estimators of . Efron’s suggestion is a scaled jackknife estimator of the skewness of :

The jackknife estimator of makes the interval more computationally costly than other intervals.

Define for any the adjusted version

The percentile interval is

Note that simplifies to (10.24) and simplies to when . While improves on by correcting the median bias, makes a further correction for skewness.

The interval is only well-defined for values of such that . (Or equivalently, if for and for .)

The interval, like the and percentile intervals, is transformation-respecting. Thus if is the interval for , then is the interval for when is monotone.

We now give a justification for the interval. The most difficult feature to understand is the estimator for . This involves higher-order approximations which are too advanced for our treatment, so we instead refer readers to Chapter of Shao and Tu (1995) and simply assume that is known.

We now show that assumption (10.28) with known implies that has exact coverage. The argument is essentially the same as that given in the previous section. Assumption (10.28) implies that the bootstrap distribution satisfies

Evaluating at and inverting we obtain (10.27) which is the same as for the BC interval. Thus the estimator (10.23) is consistent as and we can treat as if it were known.

From (10.29) we deduce that

This shows that equals the bootstrap quantile. Hence we can write as

It has coverage probability

The second equality applies the transformation . The fourth equality uses the model (10.28) and the fact . This shows that the interval has exact coverage under the assumption (10.28) with known.

The bootstrap percentile intervals for the four estimators are reported in Table 13.2. They are generally similar to the BC intervals, though the intervals for and are slightly shifted to the right.

In Stata, intervals can be obtained by using the command estat bootstrap, bca or the command estat bootstrap, all after an estimation command which calculates standard errors via the bootstrap using the bca option.

Percentile-t Interval

In many cases we can obtain improvement in accuracy by bootstrapping a studentized statistic such as a t-ratio. Let be an estimator of a scalar parameter and a standard error. The sample t-ratio is

The bootstrap t-ratio is

where is the standard error calculated on the bootstrap sample. Notice that the bootstrap t-ratio is centered at the parameter estimator . This is because is the “true value” in the bootstrap universe.

The percentile-t interval is formed using the distribution of . This can be calculated via the bootstrap algorithm. On each bootstrap sample the estimator and its standard error are calculated, and the t-ratio calculated and stored. This is repeated times. The quantile is estimated by the empirical quantile (or any quantile estimator) from the bootstrap draws of .

The bootstrap percentile-t confidence interval is defined as

The form may appear unusual when compared with the percentile interval. The left endpoint is determined by the upper quantile of the distribution of , and the right endpoint is determined by the lower quantile. As we show below, this construction is important for the interval to have correct coverage when the distribution is not symmetric.

When the estimator is asymptotically normal and the standard error a reliable estimator of the standard deviation of the distribution we would expect the t-ratio to be roughly approximated by the normal distribution. In this case we would expect . Departures from this baseline occur as the distribution becomes skewed or fat-tailed. If the bootstrap quantiles depart substantially from this baseline it is evidence of substantial departure from normality. (It may also indicate a programming error, so in these cases it is wise to triple-check!)

The percentile-t has the following advantages. First, when the standard error is reasonably reliable, the percentile-t bootstrap makes use of the information in the standard error, thereby reducing the role of the bootstrap. This can improve the precision of the method relative to other methods. Second, as we show later, the percentile-t intervals achieve higher-order accuracy than the percentile and BC percentile intervals. Third, the percentile-t intervals correspond to the set of parameter values “not rejected” by one-sided t-tests using bootstrap critical values (bootstrap tests are presented in Section 10.21).

The percentile-t interval has the following disadvantages. First, they may be infeasible when standard error formula are unknown. Second, they may be practically infeasible when standard error calculations are computationally costly (since the standard error calculation needs to be performed on each bootstrap sample). Third, the percentile-t may be unreliable if the standard errors are unreliable and thus add more noise than clarity. Fourth, the percentile-t interval is not translation preserving, unlike the percentile, percentile, and percentile intervals.

It is typical to calculate percentile-t intervals with t-ratios constructed with conventional asymptotic standard errors. But this is not the only possible implementation. The percentile-t interval can be constructed with any data-dependent measure of scale. For example, if is a two-step estimator for which it is unclear how to construct a correct asymptotic standard error, but we know how to calculate a standard error appropriate for the second step alone, then can be used for a percentile-t-type interval as described above. It will not possess the higher-order accuracy properties of the following section, but it will satisfy the conditions for first-order validity.

Furthermore, percentile-t intervals can be constructed using bootstrap standard errors. That is, the statistics and can be computed using bootstrap standard errors . This is computationally costly as it requires what we call a “nested bootstrap”. Specifically, for each bootstrap replication, a random sample is drawn, the bootstrap estimate computed, and then additional bootstrap sub-samples drawn from the bootstrap sample to compute the bootstrap standard error for the bootstrap estimate . Effectively bootstrap samples are drawn and estimated, which increases the computational requirement by an order of magnitude.

We now describe the distribution theory for first-order validity of the percentile-t bootstrap.

First, consider the smooth function model, where and with bootstrap analogs and . From Theorems , and

and

where . This shows that the sample and bootstrap t-ratios have the same asymptotic distribution.

This motivates considering the broader situation where the sample and bootstrap t-ratios have the same asymptotic distribution but not necessarily normal. Thus assume that

for some continuous distribution . (10.31) implies that the quantiles of converge in probability to those of , that is where is the quantile of . This and (10.30) imply

Thus the percentile-t is asymptotically valid. Theorem If (10.30) and (10.31) hold where is continuously distributed, then as

The bootstrap percentile-t intervals for the four estimators are reported in Table 13.2. They are similar but somewhat different from the percentile-type intervals, and generally wider. The largest difference arises with the interval for which is noticably wider than the other intervals.

Percentile-t Asymptotic Refinement

This section uses the theory of Edgeworth and Cornish-Fisher expansions introduced in Chapter 9.8-9.10 of Probability and Statistics for Economists. This theory will not be familiar to most students. If you are interested in the following refinement theory it is advisable to start by reading these sections of Probability and Statistics for Economists.

The percentile-t interval can be viewed as the intersection of two one-sided confidence intervals. In our discussion of Edgeworth expansions for the coverage probability of one-sided asymptotic confidence intervals (following Theorem in the context of functions of regression coefficients) we found that one-sided asymptotic confidence intervals have accuracy to order . We now show that the percentile-t interval has improved accuracy.

Theorem of Probability and Statistics for Economists showed that the Cornish-Fisher expansion for the quantile of a t-ratio in the smooth function model takes the form

where is an even polynomial of order 2 with coefficients depending on the moments up to order 8. The bootstrap quantile has a similar Cornish-Fisher expansion

where is the same as except that the population moments are replaced by the corresponding sample moments. Sample moments are estimated at the rate . Thus we can replace with without affecting the order of this expansion:

This shows that the bootstrap quantiles of the studentized t-ratio are within of the exact quantiles .

By the Edgeworth expansion Delta method (Theorem of Probability and Statistics for Economists), and have the same Edgeworth expansion to order . Thus

Thus the coverage of the percentile-t interval is

This is an improved rate of convergence relative to the one-sided asymptotic confidence interval. Theorem Under the assumptions of Theorem of Probability and Statistics for Economists, .

The following definition of the accuracy of a confidence interval is useful.

Definition 10.3 A confidence set for is -order accurate if

Examining our results we find that one-sided asymptotic confidence intervals are first-order accurate but percentile-t intervals are second-order accurate. When a bootstrap confidence interval (or test) achieves high-order accuracy than the analogous asymptotic interval (or test), we say that the bootstrap method achieves an asymptotic refinement. Here, we have shown that the percentile-t interval achieves an asymptotic refinement.

In order to achieve this asymptotic refinement it is important that the t-ratio (and its bootstrap counter-part ) are constructed with asymptotically valid standard errors. This is because the first term in the Edgeworth expansion is the standard normal distribution and this requires that the t-ratio is asymptotically normal. This also has the practical finite-sample implication that the accuracy of the percentile-t interval in practice depends on the accuracy of the standard errors used to construct the t-ratio.

We do not go through the details, but normal-approximation bootstrap intervals, percentile bootstrap intervals, and bias-corrected percentile bootstrap intervals are all first-order accurate and do not achieve an asymptotic refinement.

The interval, however, can be shown to be asymptotically equivalent to the percentile-t interval, and thus achieves an asymptotic refinement. We do not make this demonstration here as it is advanced. See Section 3.10.4 of Hall (1992).

| Peter Gavin Hall (1951-2016) of Australia was one of the most influential and |

| prolific theoretical statisticians in history. He made wide-ranging contributions. |

| Some of the most relevant for econometrics are theoretical investigations of |

| bootstrap methods and nonparametric kernel methods. |

Bootstrap Hypothesis Tests

To test the hypothesis against the most common approach is a t-test. We reject in favor of for large absolute values of the t-statistic where is an estimator of and is a standard error for . For a bootstrap test we use the bootstrap algorithm to calculate the critical value. The bootstrap algorithm samples with replacement from the dataset. Given a bootstrap sample the bootstrap estimator and standard error are calculated. Given these values the bootstrap -statistic is . There are two important features about the bootstrap t-statistic. First, is centered at the sample estimate , not at the hypothesized value . This is done because is the true value in the bootstrap universe, and the distribution of the t-statistic must be centered at the true value within the bootstrap sampling framework. Second, is calculated using the bootstrap standard error . This allows the bootstrap to incorporate the randomness in standard error estimation.

The failure to properly center the bootstrap statistic at is a common error in applications. Often this is because the hypothesis to be tested is , so the test statistic is . This intuitively suggests the bootstrap statistic , but this is wrong. The correct bootstrap statistic is

The bootstrap algorithm creates draws . The bootstrap critical value is , where is the quantile of the absolute values of the bootstrap t-ratios . For a test we reject in favor of if and fail to reject if .

It is generally better to report p-values rather than critical values. Recall that a p-value is where is the null distribution of the statistic . The bootstrap p-value is defined as , where is the bootstrap distribution of . This is estimated from the bootstrap algorithm as

the percentage of bootstrap t-statistics that are larger than the observed t-statistic. Intuitively, we want to know how “unusual” is the observed statistic when the null hypothesis is true. The bootstrap algorithm generates a large number of independent draws from the distribution (which is an approximation to the unknown distribution of ). If the percentage of the that exceed is very small (say ) this tells us that is an unusually large value. However, if the percentage is larger, say , then we cannot interpret as unusually large.

If desired, the bootstrap test can be implemented as a one-sided test. In this case the statistic is the signed version of the t-ratio, and bootstrap critical values are calculated from the upper tail of the distribution for the alternative , and from the lower tail for the alternative . There is a connection between the one-sided tests and the percentile-t confidence interval. The latter is the set of parameter values which are not rejected by either one-sided bootstrap t-test.

Bootstrap tests can also be conducted with other statistics. When standard errors are not available or are not reliable we can use the non-studentized statistic . The bootstrap version is . Let be the quantile of the bootstrap statistics . A bootstrap test rejects if . The bootstrap p-value is

Theorem If (10.30) and (10.31) hold where is continuously distributed, then the bootstrap critical value satisfies where is the quantile of . The bootstrap test “Reject in favor of if ” has asymptotic size as . In the smooth function model the t-test (with correct standard errors) has the following performance.

Theorem Under the assumptions of Theorem of Probability and Statistics for Economists,

where is the quantile of . The asymptotic test “Reject in favor of if ” has accuracy

and the bootstrap test “Reject in favor of if ” has accuracy

This shows that the bootstrap test achieves a refinement relative to the asymptotic test.

The reasoning is as follows. We have shown that the Edgeworth expansion for the absolute t-ratio takes the form

This means the asymptotic test has accuracy of order .

Given the Edgeworth expansion, the Cornish-Fisher expansion for the quantile of the distribution of takes the form

The bootstrap quantile has the Cornish-Fisher expansion

where is the same as except that the population moments are replaced by the corresponding sample moments. The bootstrap test has rejection probability, using the Edgeworth expansion Delta method (Theorem of of Probability and Statistics for Economists)

as claimed.

Wald-Type Bootstrap Tests

If is a vector then to test against at size , a common test is based on the Wald statistic where is an estimator of and is a covariance matrix estimator. For a bootstrap test we use the bootstrap algorithm to calculate the critical value. The bootstrap algorithm samples with replacement from the dataset. Given a bootstrap sample the bootstrap estimator and covariance matrix estimator are calculated. Given these values the bootstrap Wald statistic is

As for the t-test it is essential that the bootstrap Wald statistic is centered at the sample estimator instead of the hypothesized value . This is because is the true value in the bootstrap universe.

Based on bootstrap replications we calculate the quantile of the distribution of the bootstrap Wald statistics . The bootstrap test rejects in favor of if . More commonly, we calculate a bootstrap p-value. This is

The asymptotic performance of the Wald test mimics that of the t-test. In general, the bootstrap Wald test is first-order correct (achieves the correct size asymptotically) and under conditions for which an Edgeworth expansion exists, has accuracy

and thus achieves a refinement relative to the asymptotic Wald test.

If a reliable covariance matrix estimator is not available a Wald-type test can be implemented with any positive-definite weight matrix instead of . This includes simple choices such as the identity matrix. The bootstrap algorithm can be used to calculate critical values and -values for the test. So long as the estimator has an asymptotic distribution this bootstrap test will be asymptotically firstorder valid. The test will not achieve an asymptotic refinement but provides a simple method to test hypotheses when covariance matrix estimates are not available.

Criterion-Based Bootstrap Tests

A criterion-based estimator takes the form

for some criterion function . This includes least squares, maximum likelihood, and minimum distance. Given a hypothesis where , the restricted estimator which satisfies is

A criterion-based statistic to test is

A criterion-based test rejects for large values of . A bootstrap test uses the bootstrap algorithm to calculate the critical value.

In this context we need to be a bit thoughtful about how to construct bootstrap versions of . It might seem natural to construct the exact same statistic on the bootstrap samples as on the original sample, but this is incorrect. It makes the same error as calculating a t-ratio or Wald statistic centered at the hypothesized value. In the bootstrap universe, the true value of is not , rather it is . Thus when using the nonparametric bootstrap, we want to impose the constraint to obtain the bootstrap version of .

Thus, the correct way to calculate a bootstrap version of is as follows. Generate a bootstrap sample by random sampling from the dataset. Let be the the bootstrap version of the criterion. On a bootstrap sample calculate the unrestricted estimator and the restricted version where . The bootstrap statistic is

Calculate on each bootstrap sample. Take the quantile . The bootstrap test rejects in favor of if . The bootstrap p-value is

Special cases of criterion-based tests are minimum distance tests, tests, and likelihood ratio tests. Take the F test for a linear hypothesis . The statistic is

where is the unrestricted estimator of the error variance, is the restricted estimator, is the number of restrictions and is the number of estimated coefficients. The bootstrap version of the statistic is

where is the unrestricted estimator on the bootstrap sample, and is the restricted estimator which imposes the restriction .

Take the likelihood ratio (LR) test for the hypothesis . The LR test statistic is

where is the unrestricted MLE and is the restricted MLE (imposing ). The bootstrap version is

where is the log-likelihood function calculated on the bootstrap sample, is the unrestricted maximizer, and is the restricted maximizer imposing the restriction .

Parametric Bootstrap

Throughout this chapter we have described the most popular form of the bootstrap known as the nonparametric bootstrap. However there are other forms of the bootstrap algorithm including the parametric bootstrap. This is appropriate when there is a full parametric model for the distribution as in likelihood estimation.

First, consider the context where the model specifies the full distribution of the random vector , e.g. where the distribution function is known but the parameter is unknown. Let be an estimator of such as the maximum likelihood estimator. The parametric bootstrap algorithm generates bootstrap observations by drawing random vectors from the distribution function . When this is done, the true value of in the bootstrap universe is . Everything which has been discussed in the chapter can be applied using this bootstrap algorithm.

Second, consider the context where the model specifies the conditional distribution of the random vector given the random vector , e.g. . An example is the normal linear regression model, where . In this context we can hold the regressors fixed and then draw the bootstrap observations from the conditional distribution . In the example of the normal regression model this is equivalent to drawing a normal error and then setting . Again, in this algorithm the true value of is and everything which is discussed in this chapter can be applied as before.

Third, consider tests of the hypothesis . In this context we can also construct a restricted estimator (for example the restricted MLE) which satisfies the hypothesis . Then we can generate bootstrap samples by simulating from the distribution , or in the conditional context from . When this is done the true value of in the bootstrap is which satisfies the hypothesis. So in this context the correct values of the bootstrap statistics are

and

where is the unrestricted estimator on the bootstrap sample and is the restricted estimator which imposes the restriction .

The primary advantage of the parametric bootstrap (relative to the nonparametric bootstrap) is that it will be more accurate when the parametric model is correct. This may be quite important in small samples. The primary disadvantage of the parametric bootstrap is that it can be inaccurate when the parametric model is incorrect.

How Many Bootstrap Replications?

How many bootstrap replications should be used? There is no universally correct answer as there is a trade-off between accuracy and computation cost. Computation cost is essentially linear in . Accuracy (either standard errors or -values) is proportional to . Improved accuracy can be obtained but only at a higher computational cost.

In most empirical research, most calculations are quick and investigatory, not requiring full accuracy. But final results (those going into the final version of the paper) should be accurate. Thus it seems reasonable to use asymptotic and/or bootstrap methods with a modest number of replications for daily calculations, but use a much larger for the final version.

In particular, for final calculations, is desired, with a minimal choice. In contrast, for daily quick calculations values as low as may be sufficient for rough estimates. A useful way to think about the accuracy of bootstrap methods stems from the calculation of pvalues. The bootstrap p-value is an average of Bernoulli draws. The variance of the simulation estimator of is , which is bounded above by . To calculate the -value within, say, of the true value with probability requires a standard error below . This is ensured if .

Stata by default sets . This is useful for verification that a program runs but is a poor choice for empirical reporting. Make sure that you set to the value you want.

Setting the Bootstrap Seed

Computers do not generate true random numbers but rather pseudo-random numbers generated by a deterministic algorithm. The algorithms generate sequences which are indistinguishable from random sequences so this is not a worry for bootstrap applications.

The methods, however, necessarily require a starting value known as a “seed”. Some packages (including Stata and MATLAB) implement this with a default seed which is reset each time the statistical package is started. This means if you start the package fresh, run a bootstrap program (e.g. a “do” file in Stata), exit the package, restart the package and then rerun the bootstrap program, you should obtain exactly the same results. If you instead run the bootstrap program (e.g. “do” file) twice sequentially without restarting the package, the seed is not reset so a different set of pseudo-random numbers will be generated and the results from the two runs will be different.