Introduction

A nonlinear regression model is a parametric regression function which is nonlinear in the parameters . We write the model as

In nonlinear regression the ordinary least squares estimator does not apply. Instead the parameters are typically estimated by nonlinear least squares (NLLS). NLLS is an m-estimator which requires numerical optimization.

We illustrate nonlinear regression with three examples.

Our first example is the Box-Cox regression model. The Box-Cox transformation (Box and Cox, 1964) for a strictly positive variable is

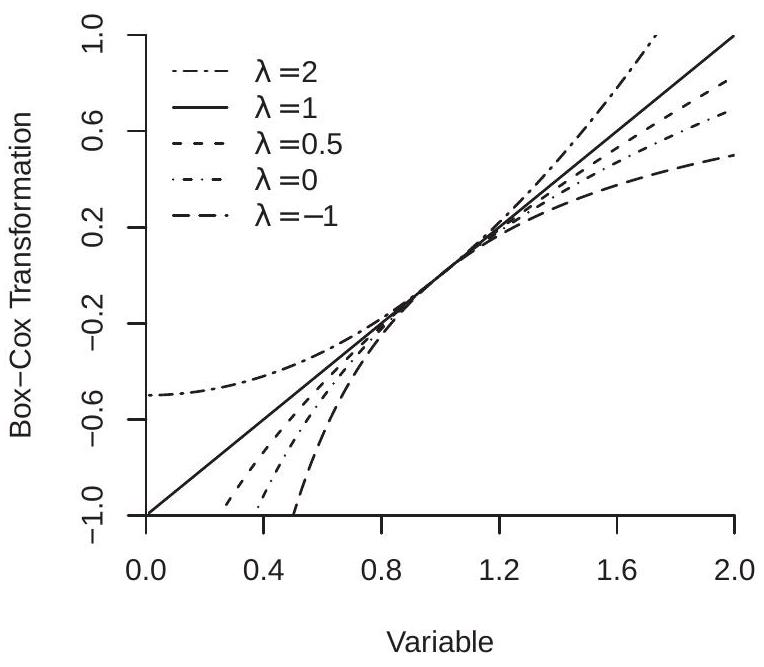

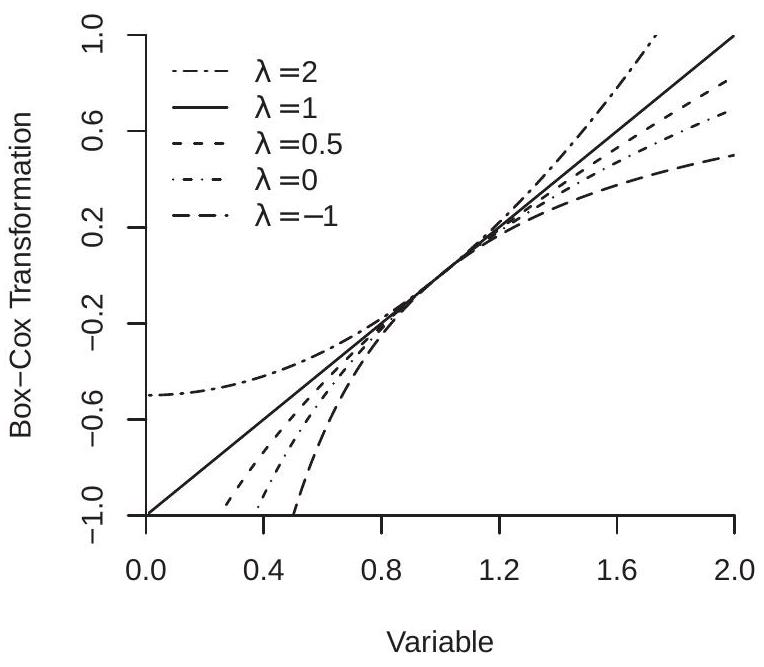

The Box-Cox transformation continuously nests linear and logarithmic functions. Figure 23.1(a) displays the Box-Cox transformation (23.1) over for , and . The parameter controls the curvature of the function.

The Box-Cox regression model is

which has parameters . The regression function is linear in but nonlinear in .

To illustrate we revisit the reduced form regression (12.87) of risk on (mortality) from Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson (2001). A reasonable question is why the authors specified the equation as a regression on (mortality) rather than on mortality. The Box-Cox regression model allows both as special cases, and equals

Our second example is a Constant Elasticity of Substitution (CES) production function, which was introduced by Arrow, Chenery, Minhas, and Solow (1961) as a generalization of the popular Cobb-Douglass production function. The CES function for two inputs is

where is heterogeneous (random) productivity, , and . The coefficient is the elasticity of scale. The coefficient is the share parameter. The coefficient is a re-writing of the elasticity of substitution between the inputs and satisfies . The elasticity satisfies if , and if . At we obtain the unit elastic Cobb-Douglas function. Setting and we obtain a linear production function. Taking the limit we obtain the Leontief production function.

Set . The framework implies the regression model

with parameters .

We illustrate CES production function estimation with a modification of Papageorgiou, Saam, and Schulte (2017). These authors estimate a CES production function for electricity production where is generation capacity using “clean” technology and is generation capacity using “dirty” technology. They estimate the model using a panel of 26 countries for the years 1995 to 2009 . Their goal was to measure the elasticity of substitution between clean and dirty electrical generation. The data file PPS2017 is an extract of the authors’ dataset.

Our third example is the regression kink model. This is essentially a piecewise continuous linear spline where the knot is treated as a free parameter. The model used in our application is the nonlinear AR(1) model

where and are the negative-part and positive-part functions, is the kink point, and the slopes are and on the two sides of the kink. The parameters are . The regression function is linear in and nonlinear in .

We illustrate the regression kink model with an application from B. E. Hansen (2017) which is a formalization of Reinhart and Rogoff (2010). The data are a time-series of annual observations on U.S. real GDP growth and the ratio of federal debt to GDP for the years 1791-2009. Reinhart-Rogoff were interested in the hypothesis that the growth rate of GDP slows when the level of debt exceeds a threshold. To illustrate, Figure 23.1 (b) displays the regression kink function. The kink is marked by the square. You can see that the function is upward sloped for and downward sloped for .

Identification

The regression model is correctly specified if there exists a parameter value such that . The parameter is point identified if is unique. In correctly-specified nonlinear regression models the parameter is point identified if there is a unique true parameter.

Assume . Since the conditional expectation is the best mean-squared predictor it follows that the true parameter satisfies the optimization expression

It is tempting to write the model as a function of the elasticity of substitution rather than its transformation . However this is unadvised as it renders the regression function more nonlinear and difficult to optimize.

- Box-Cox Transformation

.jpg)

- Regression Kink Model

Figure 23.1: Nonlinear Regression Models

where

is the expected squared error. This expresses the parameter as a function of the distribution of .

The regression model is mis-specified if there is no such that . In this case we define the pseudo-true value as the best-fitting parameter (23.5). It is difficult to give general conditions under which the solution is unique. Hence identification of the pseudo-true value under mis-specification is typically assumed rather than deduced.

Estimation

The analog estimator of the expected squared error is the sample average of squared errors

Since minimizes its analog estimator minimizes

This is called the Nonlinear Least Squares (NLLS) estimator. It includes OLS as the special case when is linear in . It is an m-estimator with .

As is a nonlinear function of in general there is no explicit algebraic expression for the solution Instead it is found by numerical minimization. Chapter 12 of Probability and Statistics for Economists provides an overview. The NLLS residuals are .

In some cases, including our first and third examples in Section 23.1, the model is linear in most of the parameters. In these cases a computational shortcut is to use nested minimization (also known as concentration or profiling). Take Example 1 (Box-Cox Regression). Given the Box-Cox parameter the regression is linear. The coefficients can be estimated by least squares, obtaining the residuals and sample concentrated average of squared errors . The latter can be minimized using one-dimensional methods. The minimizer is the NLLS estimator of . Given , the NLLS coefficient estimators are found by OLS regression of on a constant and .

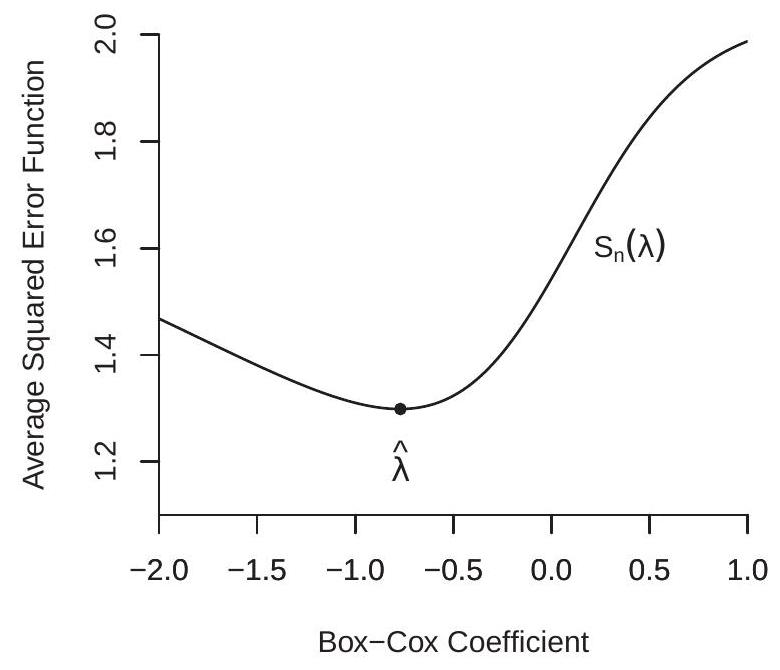

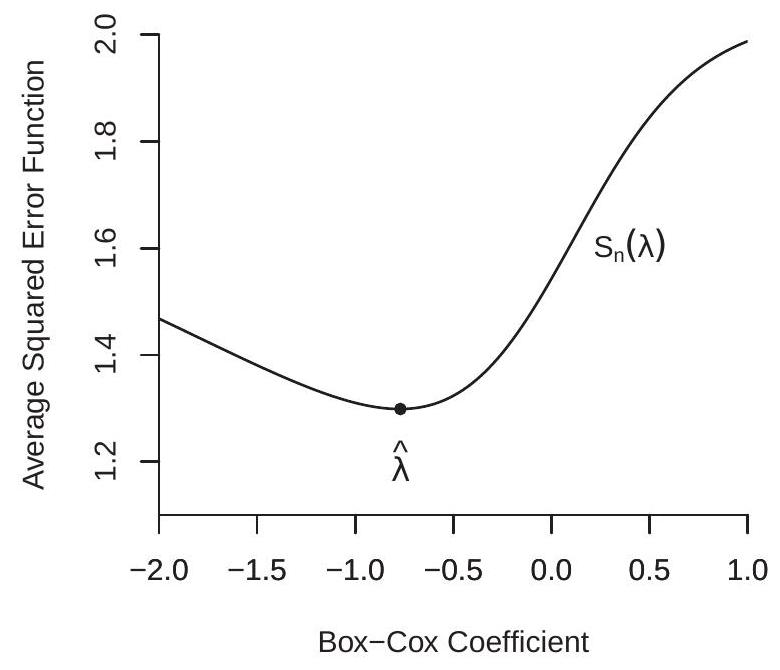

- Box-Cox Regression

.jpg)

- CES Production Function

Figure 23.2: Average of Squared Errors Functions

We illustrate with two of our examples.

Figure 23.2(a) displays the concentrated average of squared errors for the Box-Cox regression model applied to (23.2), displayed as a function of the Box-Cox parameter . You can see that is neither quadratic nor globally convex, but has a well-defined minimum at . This is a parameter value which produces a regression model considerably more curved than the logarithm specification used by Acemoglou et. al.

Figure 23.2(b) displays the average of squared errors for the CES production function application, displayed as a function of with the other parameters set at the minimizer. You can see that the minimum is obtained at . We have displayed the function by its contour surfaces. A quadratic function has elliptical contour surfaces. You can see that the function appears to be close to quadratic near the minimum but becomes increasingly non-quadratic away from the minimum.

The parameter estimates and standard errors for the three models are presented in Table 23.1. Standard error calculation will be discussed in Section 23.5. The standard errors for the Box-Cox and Regression Kink models were calculated using the heteroskedasticity-robust formula, and those for the CES production function were calculated by the cluster-robust formula, clustering by country.

Take the Box-Cox regression. The estimate shows that the estimated relationship between risk and mortality has stronger curvature than the logarithm function, and the estimate is negative as predicted. The large standard error for , however, indicates that the slope coefficient is not precisely estimated.

Take the CES production function. The estimate is positive, indicating that clean and dirty technologies are substitutes. The implied elasticity of substitution is . The estimated Table 23.1: NLLS Estimates of Example Models

| CES Production Function |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Regression Kink Regression |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

elasticity of scale is slightly above one, consistent with increasing returns to scale. The share parameter for clean technology is somewhat less than one-half, indicating that dirty technology is the dominating input.

Take the regression kink function. The estimated slope of GDP growth for low debt levels is positive, and the estimated slope for high debt levels is negative. This is consistent with the Reinhart-Rogoff hypothesis that high debt levels lead to a slowdown in economic growth. The estimated kink point is which is considerably lower than the postulated kink point suggested by Reinhart-Rogoff based on their informal analysis.

Interpreting conventional t-ratios and p-values in nonlinear models should be done thoughtfully. This is a context where the annoying empirical custom of appending asterisks to all “significant” coefficient estimates is particularly inappropriate. Take, for example, the CES estimates in Table 23.1. The “t-ratio” for is for the test of the hypothesis that , which is a meaningless hypothesis. Similarly the t-ratio for is for an uninteresting hypothesis. It does not make sense to append asterisks to these estimates and describe them as “significant” as there is no reason to take 0 as an interesting value for the parameter. Similarly in the Box-Cox regression there is no reason to take as an important hypothesis. In the Regression Kink model the hypothesis is generally meaningless and could easily lie outside the parameter space.

Asymptotic Distribution

We first consider the consistency of the NLLS estimator. We appeal to Theorems and for m-estimators.

Assumption $23.1

are i.i.d.

is continuous in with probability one.

.

with .

is compact.

For all .

Assumptions 1-4 are fairly standard. Assumption 5 is not essential but simplifies the proof. Assumption 6 is critical. It states that the minimizer is unique.

Theorem 23.1 Consistency of NLLS Estimator If Assumption holds then as .

We next discuss the asymptotic distribution for differentiable models. We first present the main result, then discuss the assumptions. Set , and . Define and

Assumption For some neighborhood of ,

.

.

and are differentiable in .

, and for .

.

is in the interior of .

Assumption 1 imposes that the model is correctly specified. If we relax this assumption the asymptotic distribution is still normal but the covariance matrix changes. Assumption 2 is a moment bound needed for asymptotic normality. Assumption 3 states that the regression function is second-order differentiable. This can be relaxed but with a complication of the conditions and derivation. Assumption 4 states moment bounds on the regression function and its derivatives. Assumption 5 states that the “linearized regressor” has a full rank population design matrix. If this assumption fails then will be multicollinear. Assumption 6 requires that the parameters are not on the boundary of the parameter space. This is important as otherwise the sampling distribution will be asymmetric.

Theorem $23.2 Asymptotic Normality of NLLS Estimator If Assumptions and hold then as , where

Theorem shows that under general conditions the NLLS estimator has an asymptotic distribution with similar structure to that of the OLS estimator. The estimator converges at a conventional rate to a normal distribution with a sandwich-form covariance matrix. Furthermore, the asymptotic variance is identical to that in a hypothetical OLS regression with the linearized regressor . Thus, asymptotically, the distribution of NLLS is identical to a linear regression.

The asymptotic distribution simplifies under conditional homoskedasticity. If then the asymptotic variance is .

Covariance Matrix Estimation

The asymptotic covariance matrix is estimated similarly to linear regression with the adjustment that we use an estimate of the linearized regressor . This estimate is

It is best if the derivative is calculated algebraically but a numerical derivative (a discrete derivative) can substitute.

Take, for example, the Box-Cox regression model for which . We calculate that for

For the third entry is . The estimate is obtained by replacing with the estimator . Hence for

The covariance matrix components are estimated as

where are the NLLS residuals. Standard errors are calculated conventionally as the square roots of the diagonal elements of .

If the error is homoskedastic the covariance matrix can be estimated using the formula

If the observations satisfy cluster dependence then a standard cluster variance estimator can be used, again treating the linearized regressor estimate as the effective regressor.

To illustrate, standard errors for our three estimated models are displayed in Table 23.1. The standard errors for the first and third models were calculated using the formula (23.6). The standard errors for the CES model were clustered by country.

In small samples the standard errors for NLLS may not be reliable. An alternative is to use bootstrap methods for inference. The nonparametric bootstrap draws with replacement from the observation pairs to create bootstrap samples, to which NLLS is applied to obtain bootstrap parameter estimates . From we can calculate bootstrap standard errors and/or bootstrap confidence intervals, for example by the bias-corrected percentile method.

Panel Data

Consider the nonlinear regression model with an additive individual effect

To eliminate the individual effect we can apply the within or first-differencing transformations. Applying the within transformation we obtain

where

using the panel data notation. Thus is the within transformation applied to . It is not . Equation (23.7) is a nonlinear panel model. The coefficient can be estimated by NLLS. The estimator is appropriate when is strictly exogenous, as is a function of for all time periods.

An alternative is to apply the first-difference transformation. Thus yields

where . Equation (23.8) can be estimated by NLLS. Again this requires that is strictly exogenous for consistent estimation.

If the regressors contains a lagged dependent variable then NLLS is not an appropriate estimator. GMM can be applied to (23.8) similar to linear dynamic panel regression models.

Threshold Models

An extreme example of nonlinear regression is the class of threshold regression models. These are discontinuous regression models where the kink points are treated as free parameters. They have been used succesfully in economics to model threshold effects and tipping points. They are also the core tool for the modern machine learning methods of regression trees and random forests. In this section we provide a review.

A threshold regression model takes the form

where and are and , respectively, and is scalar. The variable is called the threshold variable and is called the threshold.

Typically, both and contain an intercept, and and are subsets of . In the latter case is the change in the slope at the threshold. The threshold variable should be either continuously distributed or ordinal.

In a full threshold specification . In this case all coefficients switch at the threshold. This regression can alternatively be written as

where and .

A simple yet full threshold model arises when there is only a single regressor . The regression can be written as

This resembles a Regression Kink model, but is more general as it allows for a discontinuity at . The Regression Kink model imposes the restriction .

A threshold model is most suitable for a context where an economic model predicts a discontinuity in the CEF. It can also be used as a flexible approximation for a context where it is believed the CEF has a sharp nonlinearity with respect to one variable, or has sharp interaction effects. The Regression Kink model, for example, does not allow for kink interaction effects.

The threshold model is critically dependent on the choice of threshold variable . This variable controls the ability of the regression model to display nonlinearity. In principle this can be generalized by incorporating multiple thresholds in potentially different variables but this generalization is limited by sample size and information.

The threshold model is linear in the coefficients and nonlinear in . The parameter is of critical importance as it determines the model’s nonlinearity - the sample split.

Many empirical applications estimate threshold models using informal ad hoc methods. What you may see is a splitting of the sample into “subgroups” based on regressor characteristics. When the latter split is based on a continuous regressor the split point is exactly a threshold parameter. When you see such tables it is prudent to be skeptical. How was this threshold parameter selected? Based on intuition? Or based on data exploration? If the former do you expect the results to be informative? If the latter should you trust the reported tests?

To illustrate threshold regression we review an influential paper by Card, Mas and Rothstein (2008). They were interested in the process of racial segregation in U.S. cities. A common hypothesis concerning the behavior of white Americans is that they are only comfortable living in a neighborhood if it has a small percentage of minority residents. A simple model of this behavior (explored in their paper) predicts that this preference leads to an unstable mixed-race equilibrium in the fraction of minorities. They call this equilibrium the tipping point. If the minority fraction exceeds this tipping point the outcome will change discontinuously. The economic mechanism is that if minorities move into a neighborhood at a roughly continuous rate, when the tipping point is reached there will be a surge in exits by white residents who elect to move due to their discomfort. This predicts a threshold regression with a discontinuity at the tipping point. The data file CMR2008 is an abridged version of the authors’ dataset.

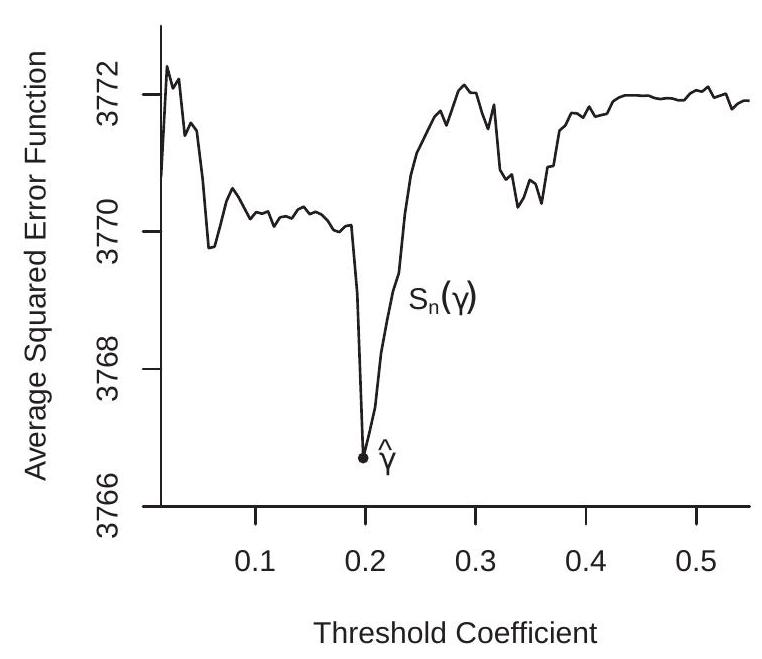

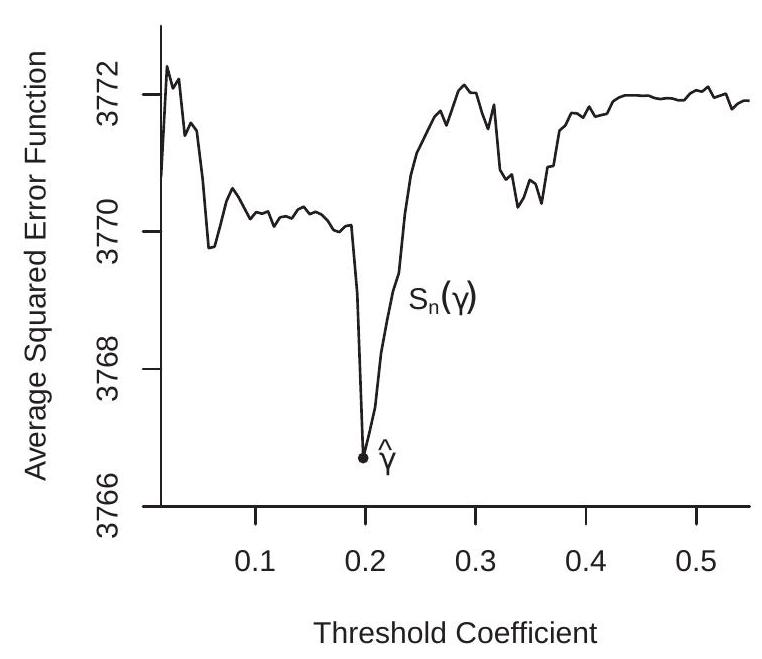

- Estimation Criterion

.jpg)

- Threshold Regression Estimates

Figure 23.3: Threshold Regression - Card-Mas-Rothstein (2008) Model

The authors use a specification similar to the following

where is the city (MSA), is a census tract within the city, is the time period (decade), is the white population percentage change in the tract over the decade, is the fraction of minorties in the tract, is a fixed effect for the city, and are tract-level regression controls. The sample is based on Census data which is collected at ten-year intervals. They estimate models for three decades; we focus on 1970-1980. Thus is the change in white population over the period 1970-1980 and the remaining variables are for 1970 . The controls used in the regression are the unemployment rate, the log mean family income, housing vacancy rate, renter share, fraction of homes in single-unit buildings, and fraction of workers who commute by public transport. This model has observations and cities. This specification allows the relationship between and to be nonlinear (a quadratic) with a discontinuous shift in the intercept and slope at the threshold. The authors’ major prediction is that should be large and negative. The threshold parameter is the minority fraction which triggers discontinuous white outward migration.

Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA). The authors use the 104 MSAs with at least 100 census tracts. As the threshold regression model is an explicit nonlinear regression, the appropriate estimation method is NLLS. Since the model is linear in all coefficients except for , the best computational technique is concentrated least squares. For each the model is linear and the coefficients can be estimated by least squares. This produces a concentrated average of squared errors which can be minimized to find the NLLS estimator . To illustrate, the concentrated least squares criterion for the Card-Mas-Rothstein dataset is displayed in Figure 23.3(a). As you can see, the criterion is highly non-smooth. This is typical in threshold applications. Consequently, the criterion needs to be minimized by grid search. The criterion is a step function with a step at each observation. A full search would calculate for equalling each value of in the sample. A simplification (which we employ) is to calculate the criterion at a smaller number of gridpoints. In our illustration we use 100 gridpoints equally-spaced between the and quantiles of . (These quantiles are the boundaries of the displayed graph.) What you can see is that the criterion is generally lower for values of between and , and especially lower for values of near . The minimum is obtained at . This is the NLLS estimator. In the context of the application this means that the point estimate of the tipping point is , which means that when the neighborhood minority fraction exceeds white households discontinuously change their behavior. The remaining NLLS estimates are obtained by least squares regression (23.9) setting .

Our estimates are reported in Table 23.2. Following Card, Mas, and Rothstein (2008) the standard errors are clustered by city (MSA). Examining Table we can see that the estimates suggest that neighborhood declines in the white population were increasing in the minority fraction, with a sharp and accelerating decline above the tipping point of . The estimated discontinuity is . This is nearly identical to the estimate obtained by Card, Mas and Rothstein (2008) using an ad hoc estimation method.

The white population was also decreasing in response to the unemployment rate, the renter share, and the use of public transportation, but increasing in response to the vacancy rate. Another interesting observation is that despite the fact that the sample has a very large number of observations the standard errors for the parameter estimates are rather large indicating considerable imprecision. This is mostly due to the clustered covariance matrix calculation as there are only clusters.

The asymptotic theory of threshold regression is non-standard. Chan (1993) showed that under correct specification the threshold estimator converges in probability to at the fast rate and that the other parameter estimators have conventional asymptotic distributions, justifying the standard errors as reported in Table 23.2. He also showed that the threshold estimator has a non-standard asymptotic distribution which cannot be used for confidence interval construction.

B. E. Hansen (2000) derived the asymptotic distribution of and associated test statistics under a “small threshold effect” asymptotic framework for a continuous threshold variable . This distribution theory permits simple construction of an asymptotic confidence interval for . In brief, he shows that under correct specification, independent observations, and homoskedasticity, the F statistic for testing

Using the 1970-1980 sample and model (23.9).

It is important that the search be constrained to values of which lie well within the support of the threshold variable. Otherwise the regression may be infeasible. The required degree of trimming (away from the boundaries of the support) depends on the individual application.

It is not clear to me whether clustering is appropriate in this application. One motivation for clustering is inclusion of fixed effects as this induces correlation across observations within a cluster. However in this case the typical number of observations per cluster is several hundred so this correlation is near zero. Another motivation for clustering is that the regression error (the unobserved factors for changes in white population) is correlated across tracts within a city. While it may be expected that attitudes towards minorities among whites may be correlated within a city, it seems less clear that we should expect unconditional correlation in population changes. Table 23.2: Threshold Estimates: Card-Mas-Rothstein (2008) Model

| Intercept Change |

|

|

| Slope Change |

|

|

| Minority Fraction |

|

|

| Minority Fraction |

|

|

| Unemployment Rate |

|

|

| Mean Family Income) |

|

|

| Housing Vacancy Rate |

|

|

| Renter Share |

|

|

| Fraction Single-Unit |

|

|

| Fraction Public Transport |

|

|

| Intercept |

|

na |

| MSA Fixed Effects |

yes |

|

| Threshold |

|

|

| Confidence Interval |

|

|

| Number of MSAs |

104 |

|

| Number of observations |

35,656 |

|

the hypothesis has the asymptotic distribution

where . The quantile of can be found by solving , and equals . For example, and .

Based on test inversion a valid asymptotic confidence interval for is the set of statistics which are less than and equals

This is constructed numerically by grid search. In our example . This is a narrow confidence interval. However, this interval does not take into account clustered dependence. Based on Hansen’s theory we can expect that under cluster dependence the asymptotic distribution needs to be re-scaled. This will result in replacing in the above formula with for some adjustment factor . This will widen the confidence interval. Based on the shape of Figure the adjusted confidence interval may not be too wide. However this is a conjecture as the theory has not been worked out so we cannot estimate the adjustment factor .

Empirical practice and simulation results suggest that threshold estimates tend to be quite imprecise unless a moderately large sample (e.g., ) is used. The threshold parameter is identified by observations close to the threshold, not by observations far from the threshold. This requires large samples to ensure that there are a sufficient number of observations near the threshold in order to be able to pin down its location

Given the coefficient estimates the regression function can be plotted along with confidence intervals calculated conventionally. In Figure 23.3(b) we plot the estimated regression function with asymptotic confidence intervals calculated based on the covariance matrix for the estimates . The estimate does not contribute if the regression function is evaluated at mean values. We ignore estimation of the intercept as its variance is not identified under clustering dependence and we are primarily interest in the magnitude of relative comparisons. What we see in Figure 23.3(b) is that the regression function is generally downward sloped, indicating that the change in the white population is generally decreasing as the minority fraction increases, as expected. The tipping effect is visually strong. When the fraction minority crosses the tipping point there are sharp decreases in both the level and the slope of the regression function. The level of the estimated regression function also indicates that the expected change in the white population switches from positive to negative at the tipping point, consistent with the segregation hypothesis. It is instructive to observe that the confidence bands are quite wide despite the large sample. This is largely due to the decision to use a clustered covariance matrix estimator. Consequently there is considerable uncertainty in the location of the regression function. The confidence bands are widest at the estimated tipping point.

The empirical results presented in this section are distinct from, yet similar to, those reported in Card, Mas, and Rothstein (2008). This is an influential paper as it used the rigor of an economic model to give insight about segregation behavior, and used a rich detailed dataset to investigate the strong tipping point prediction.

Testing for Nonlinear Components

Identification can be tricky in nonlinear regression models. Suppose that

where is a function of and an unknown parameter . Examples for include the Box-Cox transformation and . The latter arises in the Regression Kink and threshold regression models.

The model is linear when . This is often a useful hypothesis (sub-model) to consider. For example, in the Card-Mas-Rothstein (2008) application this is the hypothesis of no tipping point which is the key issue explored in their paper.

In this section we consider tests of the hypothesis . Under the model is and both and have dropped out. This means that under the parameter is not identified. This renders standard distribution theory invalid. When the truth is the NLLS estimator of is not asymptotically normally distributed. Classical tests excessively over-reject if applied with conventional critical values.

As an example consider the threshold regression (23.9). The hypothesis of no tipping point corresponds to the joint hypothesis and . Under this hypothesis the parameter is not identified.

To test the hypothesis a standard test is to reject for large values of the F statistic

where and is the least squares coefficient from the regression of on . This is the difference between the error variance estimators based on estimates calculated under the null and alternative .

The F statistic can be written as

where

The statistic is the classical statistic for a test of when is known. We can see from this representation that is non-standard as it is the maximum over a potentially large number of statistics

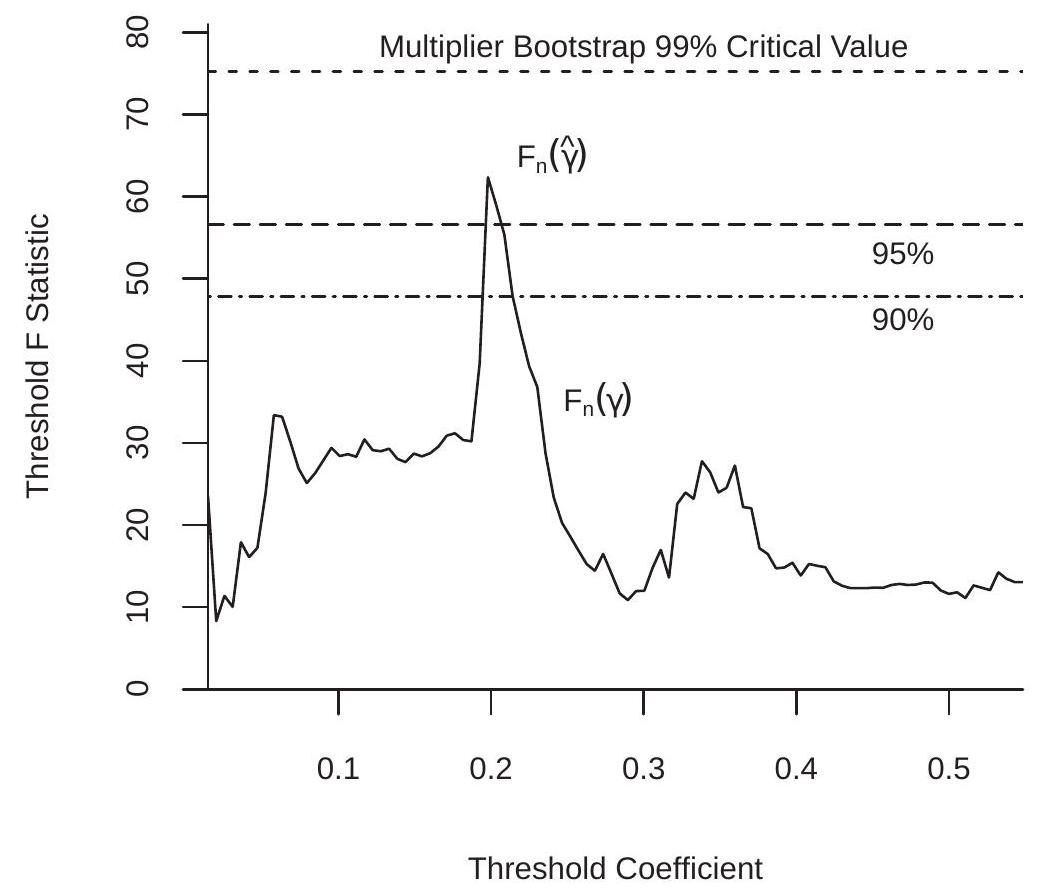

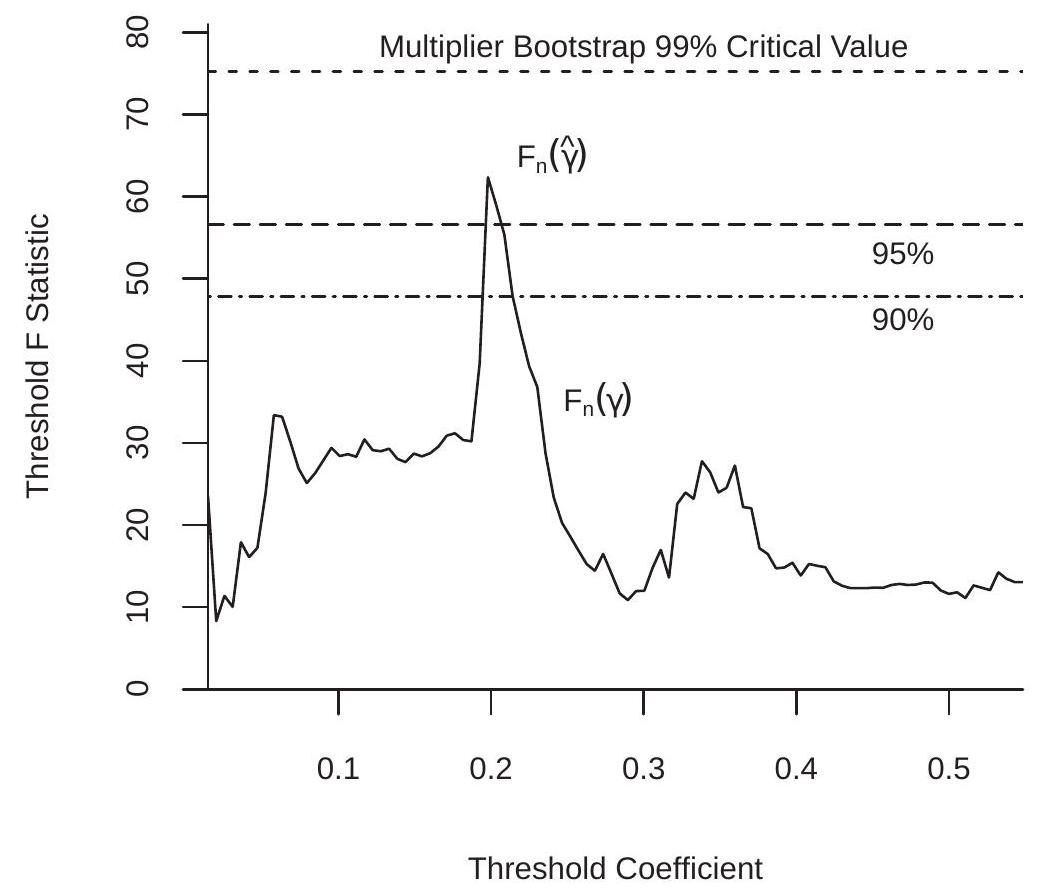

Figure 23.4: Test for Threshold Regression in CMR Model

To illustrate, Figure plots the test statistic as a function of . You can see that the function is erratic, similar to the concentrated criterion . This is sensible, because is an affine function of the inverse of . The statistic is maximized at because of this duality. The maximum value is . In this application we find . This is extremely high by conventional standards.

The asymptotic theory of the test has been worked out by Andrews and Ploberger (1994) and B. E. Hansen (1996). In particular, Hansen shows the validity of the multiplier bootstrap for calculation of p-values for independent observations. The method is as follows.

On the observations calculate the test statistic for against (or any other standard statistic such as a Wald or likelihood ratio).

For :

Generate random variables with mean zero and variance 1 (standard choices are normal and Rademacher).

Set where are the NLLS residuals.

calculate the statistic for against . 3. The multiplier bootstrap p-value is .

1. If the test is significant at level .

- Critical values can be calcualted as empirical quantiles of the bootstrap statistics .

In step you can alternatively set . Tests on are invariant to the bootstrap value of . What is important is that the bootstrap data satisfy the null hypothesis.

For clustered samples we need to make a minor modification. Write the regression by cluster as

The bootstrap method is modified by altering steps and above. Let denote the number of clusters. The modified algorithm uses the following steps.

- Generate random variables with mean zero and variance 1 .

To illustrate we apply this test to the threshold regression (23.9) estimated with the Card-Mas-Rothstein (2008) data. We use bootstrap replications. Applying the first algorithm (suitable for independent observations) the bootstrap p-value is . The critical value is , so the observed value of far exceeds this threshold. Applying the second algorithm (suitable under cluster dependence) the bootstrap p-value is . The critical value is and the is . Thus the observed value of is “significant” at the but not the level. For a sample of size this is surprisingly mild significance. These critical values are indicated on Figure by the dashed lines. The F statistic process breaks the and critical values but not the . Thus despite the visually strong evidence of a tipping effect from the previous section the statistical evidence of this effect is strong but not overwhelming.

Computation

Stata has a built-in command nl for NLLS estimation. You need to specify the nonlinear equation and give starting values for the numerical search. It is prudent to try several starting values because the algorithm is not guaranteed to converge to the global minimum.

Estimation of NLLS in R or MATLAB requires a bit more programming but is straightforward. You write a function which calculates the average squared error (or concentrated average squared error) as a function of the parameters. You then call a numerical optimizer to minimize this function. For example, in R for vector-valued parameters the standard optimizer is optim. For scalar parameters use optimize.

Technical Proofs*

Proof of Theorem 23.1. We appeal to Theorem which holds under five conditions. Conditions 1,2 , 4, and 5 are satisfied directly by Assumption 23.1, parts 1, 2, 5, and 6. To verify condition 3, observe that by the inequality (B.5) and

The right side has finite expectation under Assumptions 23.1, parts 3 and 4 . We conclude that as stated.

Proof of Theorem 23.2. We appeal to Theorem which holds under five conditions (in addition to consistency, which was established in Theorem 23.1). It is convenient to rescale the criterion so that . Then .

To show condition 1, by the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality (B.32) and Assumption 23.2.2 and 23.2.4

We next show condition 3. Using Assumption 23.2.1, we calculate that

Thus

with derivative

This exists and is continuous for under Assumption 23.2.4.

Evaluating (23.10) at we obtain

under Assumption 23.2.5. This verifies condition 2.

Condition 4 holds if is Lipschitz-continuous in . This holds because both and are differentiable in the compact set , and bounded fourth moments (Assumptions and 23.2.4) implies that the Lipschitz bound for has a finite second moment.

Condition 5 is implied by Assumption 23.2.6.

Together, the five conditions of Theorem are satisfied and the stated result follows.

Exercises

Exercise 23.1 Take the model with .

Is the CEF linear or nonlinear in ? Is this a nonlinear regression model?

Is there a way to estimate the model using linear methods? If so, explain how to obtain an estimator for .

Is your answer in part (b) the same as the NLLS estimator, or different?

Exercise 23.2 Take the model with where is the Box-Cox transformation of . (a) Is this a nonlinear regression model in the parameters ? (Careful, this is tricky.)

Exercise 23.3 Take the model with .

Are the parameters identified?

If not, what parameters are identified? How would you estimate the model?

Exercise 23.4 Take the model with .

Are the parameters identified?

Find an expression to calculate the covariance matrix of the NLLS estimatiors .

Exercise 23.5 Take the model with . Find the MLE for and .

Exercise 23.6 Take the model with , where is and is .

What relationship between and is necessary for identification of ?

Describe how to estimate by GMM.

Describe an estimator of the asymptotic covariance matrix.

Exercise 23.7 Suppose that with is the NLLS estimator, and the estimator of . You are interested in the CEF at some . Find an asymptotic confidence interval for .

Exercise 23.8 The file PSS2017 contains a subset of the data from Papageorgiou, Saam, and Schulte (2017). For a robustness check they re-estimated their CES production function using approximated capital stocks rather than capacities as their input measures. Estimate the model (23.3) using this alternative measure. The variables for , and are EG_total, EC_c_alt, and EC_d_alt, respectively. Compare the estimates with those reported in Table 23.1.

Exercise 23.9 The file RR2010 contains the U.S. observations from the Reinhart and Rogoff (2010). The data set has observations on real GDP growth, debt/GDP, and inflation rates. Estimate the model (23.4) setting as the inflation rate and as the debt ratio.

Exercise 23.10 In Exercise 9.26, you estimated a cost function on a cross-section of electric companies. Consider the nonlinear specification

This model is called a smooth threshold model. For values of much below , the variable has a regression slope of . For values much above , the regression slope is . The model imposes a smooth transition between these regimes.

The model works best when is selected so that several values (in this example, at least 10 to 15) of are both below and above . Examine the data and pick an appropriate range for .

Estimate the model by NLLS using a global numerical search over .

Estimate the model by NLLS using a concentrated numerical search over . Do you obtain the same results?

Calculate standard errors for all the parameters estimates .

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)